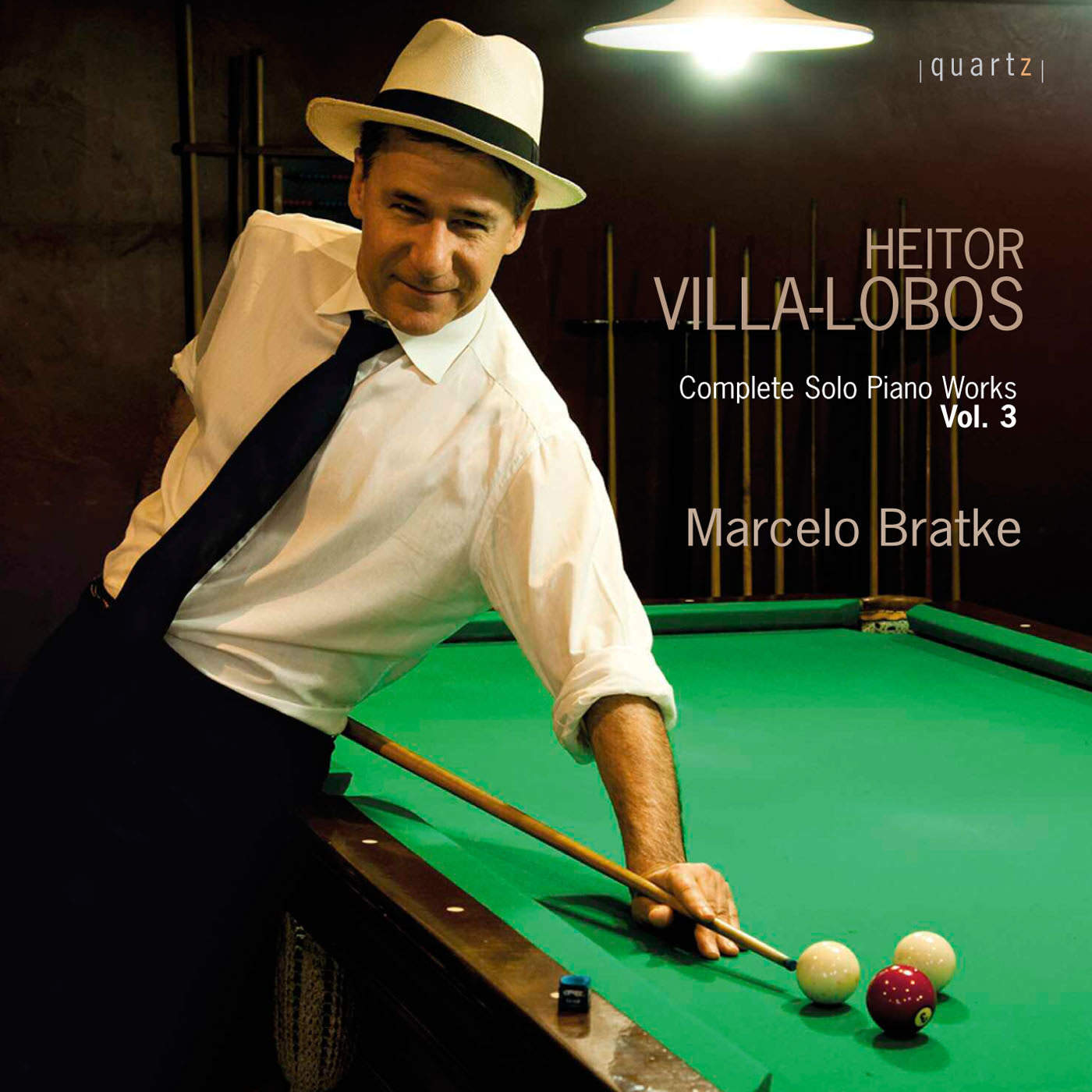

Heitor Villa-Lobos – Complete Piano Works Vol. 3

Price range: £5.99 through £11.99

PROLE DO BEBÊ NO.1

SUÍTE INFANTIL NO.1

SUÍTE INFANTIL NO 2

FRANCETTE ET PIÀ

AS TRÊS MARIAS

CARNAVAL DAS CRIANÇAS

About This Recording

Paris was the centre of the world at the turn of the 20th Century while Rio de Janeiro, a remote and exotic city in the tropics, was in the process of forming its own cultural physiognomy, marked by the fusion between European, Native-Brazilian and Afro-Brazilian cultures. This CD brings together six piano solo works written between 1912 and 1939 by Heitor Villa-Lobos: A Prole do Bebê no.1, Suítes Infantis 1 and 2, Francette et Pià, As Três Marias and Carnaval das Crianças revealing the influence the Parisian avant garde of the time had on the composer and his cross pollination with Brazilian musical elements, in the process of creating his own musical universe.Marcelo Bratke

Piano pieces formed of miniatures inspired by children’s songs and transfigured into music poetry by the musical genius of Villa-Lobos. They are very short works, only two of these miniature masterpieces last for three minutes or more. Their brevity demands concentration and requires a rigorous sense of structure. In turn, in his long compositions and fabulously entangled orchestrations, Villa-Lobos lets endless inventions collide with each other and overlap in asphyxiating orgies of sound saturated with ingenuity.

In these short piano pieces however, the composer refuses to be swept up in intellectual complexity and inspiration comes in a perfect form.

The oldest pieces are the Suítes Infantis (Children’s Suites), the first of which dates from 1912, the second from 1913.

Dating the works of Villa-Lobos is difficult. Lisa Peppercorn and her successor Mario de Andrade in a more conclusive way noted how Villa-Lobos juggled with his timelines. He altered dates, rewrote his own biography and invented earlier dates for various works to enhance his image as an early champion of the distinctive Brazilian spirit that supposedly grew up with him in his childhood days and provided the grounding and inspiration for his compositions. This was the case in Amazonas, Uirapuru and other works.

Referring to the Brazilian roots helps to explain the actual evolution over time of the piano compositions. The myths surrounding Villa-Lobos and his Brazilian heritage have to be explained before we can understand what really happened.

Mario de Andrade aptly noted that very little was distinctively “Brazilian” in the work that Villa-Lobos performed at the 1922 Week of Modern Art. Until then, says de Andrade, his compositions were permeated by “Europeanisms in terms of syntax and even Debussyisms in vocabulary, easily found in great numbers within Villa-Lobos concerts until 1923 or later.”

According to Mario de Andrade, it was the 1922 Week of Modern Art that prompted Villa-Lobos’ concern for the nationalist character of his work. However, a different explanation is much more conclusive: Villa-Lobos was to take his first trip to Europe in 1923.

The apparent paradox was that the composer discovered Brazil from his apartment on Place Saint Michel, in Paris. The Finnish musicologist Eero Tarasti outlined the occasion in his essay Villa-Lobos, ser sinfônico dos trópicos: “Upon visiting Paris and Europe in the 1920s, Villa-Lobos realized that (…) the European musical world was mainly interested in him as an interpreter of Brazilianness, with the vigorous primitive rhythms of its compositions, its harmonies, folk melodies and musical tones reflecting the varied colors of the tropics.”

It remains to be seen whether the tropics do actually have their own colors, or whether these colors are reflections from a seduced outlook. Villa-Lobos clearly decided to make the most of exoticism. Irrespective of his creative genius he then ensured his status as a tropical composer by starting to write Brazilian music in Europe. Previously he had been writing French music in Brazil.

All nationalisms are social constructs and Villa-Lobos wrapped himself in nationalist robes but there was much more to him.

The 1912 and 1913 Suítes Infantis are perfect illustrations of how Villa-Lobos immersed himself in the French culture of this period, a beautiful Ravelian spirit hovers over them. The clarity, the elegance, the sensitive originality of these inventions, their melancholy mood or their vivacity make it impossible to understand why they are so unloved by musicians and so rarely featured in programs.

Suíte Infantil no.1 (1912) has titles for each of its movements. From the beginning, a wonderful Ravelian tone is set. The dance, lullaby, children’s antics, reflections (seeming to be so dense and profound) and their rhythm or swing are sensitive and evocative. In Suíte Infantil no.2 (1913), titles are replaced by annotations for pace. Just as Ravel did with Couperin, Villa-Lobos has the shadow of an older composer resurface in the first movement, treated in line with contemporary taste. Neither of the above suites points to any nationalist content. In A Prole do Bebê no.1 (The Baby’s Family no.1) written in 1918, Villa-Lobos revives children’s songs from memory. Arthur Rubinstein premièred the work in Rio de Janeiro in 1922 and went on to play it in Paris and all over the world with O Polichinelo (Punchinello) as one of his most acclaimed encores. Through this piece, Villa-Lobos reasserted, more powerfully, his sincere love of children.

Oscar Guanabarino was a Rio de Janeiro music critic and a fierce enemy of Villa- Lobos who, in this case at least, yielded to the allure of the piece. Characterizing the stylistic nature of the work, he wrote that had the programme not named the composer, one would have thought it a new piece by Debussy written to honour Brazil, since its themes were taken from Brazilian children’s songs or folklore. Carnaval de Crianças (Children’s Carnival) (1919) was later renamed Momoprecoce when Villa-Lobos added an orchestra to lend it a monumental tone. However it is the piano-solo version of the composition that highlights its lightness and naturalness. Children in costume suggest images, the galloping horse of little Pierrot (performed at the 1922 Week of Modern Art), lashes of the devil’s whip, bells, a local reference to the carnival theme of Viva o Zé Pereira (Long Live Zé Pereira) and the harmonica, rhythms and melodies inspired by the Rio carnival of the beginning of the 20th Century. Having no children of his own, Villa-Lobos dedicated the Children’s Carnival to his nephews and nieces.

Although the nationalist project was not yet completely developed in Villa-Lobos’ mind at that time, A Prole do Bebê no.1, Carnaval das Crianças, and Suítes Infantis are in no way byproducts of French music. Listening to them gives you a sense of their originality. They were scored in the style of Debussy or Ravel but this style had become universal and composers from different countries around the world, such as de Falla and Delius, were using it to inspire and support their own creative work and talents.

Villa-Lobos gained significant prestige in the Paris of the 1920s, the period of his boldest and most creative work, before returning to a more orderly approach in the 1930s. In 1928, when the publisher Max Eschig commissioned a few works for students of the celebrated professor and pianist Marguerite Long at the Paris Conservatory, Villa-Lobos wrote one of his most charming and most original compositions, Francette et Pià. He imagined a little Indian boy called Pià befriending a little French girl, Francette. There is a “barbarian” mood from the beginning, with syncopated jazz à la Revue Nègre bringing in French children’s songs such as Au Clair de la Lune or Marlbrough s’en va-t-en guerre, reflections of Brazilian themes, the Marseillaise, and many other references scored in miraculously straightforward language.

Finally, As Três Marias (The Three Marys) of 1939, refers to the Brazilian name for the three bright stars aligned to form the belt of Orion the Hunter, strangely and magically named Alnitak, Alnilam and Mintaka. The first and last are faster, Alnilam is slow and melancholic. Their shine comes from an exquisite piano score. The composition was suggested by Edgar Varèse.

Villa-Lobos wrote a poem around these stars in which the children switch from national particularism to a broad and generous universal humanism.

Once there were three girls,the three Marys of the earthwho played and skipped aroundin the backlands of Brazil.Happily together they’d gohopping and grinningat equal distance from one anotheralong all walks of life …And for this threesometo forever become the symbolof sharing Humanity,Fate had them halt there…in the heavenly infinityto cast light on the wayof all the children on earth.Jorge Coli

Tarasti, Eero. Essay in volume 9 of the series “Presença de Villa-Lobos”, published by Museu Villa-Lobos in 1989. Translated from Portuguese for this edition.

Track Listing

-

Heitor Villa-Lobos

- PROLE DO BEBÊ NO.1 - Branquinha (A Boneca de Louça)

- PROLE DO BEBÊ NO.1 - Moreninha (A Boneca de Massa)

- PROLE DO BEBÊ NO.1 - Caboclinha (A Boneca de Barro)

- PROLE DO BEBÊ NO.1 - Mulatinha (A Boneca de Borracha)

- PROLE DO BEBÊ NO.1 - Negrinha (A Boneca de Pau)

- PROLE DO BEBÊ NO.1 - Pobrezinha (A Boneca de Trapo)

- PROLE DO BEBÊ NO.1 - O Polichinelo

- PROLE DO BEBÊ NO.1 - Bruxa (A Boneca de Pano)

- SUÍTE INFANTIL NO.1 - Bailando (Movimento de Minueto più animato.)

- SUÍTE INFANTIL NO.1 - Nenê Vai Dormir (Andante melancólico)

- SUÍTE INFANTIL NO.1 - Artimanhas (Allegretto quasi allegro)

- SUÍTE INFANTIL NO.1 - Reflexão (Allegro)

- SUÍTE INFANTIL NO.1 - No Balanço (Allegro non troppo)

- SUÍTE INFANTIL NO.2 - Allegro

- SUÍTE INFANTIL NO.2 - Andantino

- SUÍTE INFANTIL NO.2 - Allegretto

- SUÍTE INFANTIL NO.2 - Allegro non troppo

- FRANCETTE ET PIÀ - Pià est venu en France

- FRANCETTE ET PIÀ - Pià a vu Francette

- FRANCETTE ET PIÀ - Pià a parlé à Francette

- FRANCETTE ET PIÀ - Pià et Francette jouent ensemble

- FRANCETTE ET PIÀ - Francette est fâchée

- FRANCETTE ET PIÀ - Pià est parti pour la guerre

- FRANCETTE ET PIÀ - Francette est triste

- FRANCETTE ET PIÀ - Pià revient de la guerre

- FRANCETTE ET PIÀ - Francette est contente

- FRANCETTE ET PIÀ - Francette et Pià jouent pour toujours

- AS TRÊS MARIAS - Alnitak

- AS TRÊS MARIAS - Alnilam

- AS TRÊS MARIAS - Mintaka

- CARNAVAL DAS CRIANÇAS - O Ginete do Pierrozinho

- CARNAVAL DAS CRIANÇAS - O Chicote do Diabinho

- CARNAVAL DAS CRIANÇAS - A Manhã do Pierrete

- CARNAVAL DAS CRIANÇAS - Os Guizos do Dominozinho

- CARNAVAL DAS CRIANÇAS - As Peripécias do Trapeirozinho

- CARNAVAL DAS CRIANÇAS - As Traquinices do Mascarado Mignon

- CARNAVAL DAS CRIANÇAS - A Gaita de um Precoce Fantasiado

- CARNAVAL DAS CRIANÇAS - A Folia de um Bloco Infantil