Alexander Glazunov: Piano Sonatas

Price range: £7.99 through £16.99

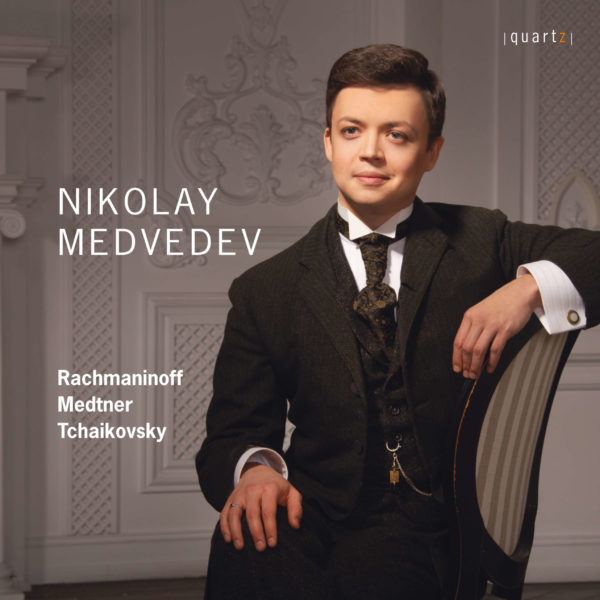

Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov was undoubtedly the most gifted Russian composer of his generation – that is to say, those born during the 1860s – and his profound musical aptitude led him to take full advantage of the educational facilities underpinning the burgeoning interest in the arts that grew exponentially in Russia during the second half of the 19th-century. He was not alone, but Glazunov’s superlative gifts did not lead him initially to a conservatoire. He began musical studies privately with Rimsky-Korsakov (twenty-one years his senior) rather than enter the St Petersburg Academy as just another gifted student. Presented here by pianist Nikolay Medvedev.

About This Recording

In considering the broad sweep of the creative arts during the last half-millennium, particularly the various aesthetic movements that are taken to define certain periods, it is undoubtedly true to say that music has often tended to lag behind the other arts. What is termed the broad Romantic movement in the humanities came later to music than it did to painting, drama, literature and other disciplines. In Russia, it was the comparatively later establishment of music colleges by the brothers Anton and Nicholas Rubinstein in St Petersburg and Moscow in the 1860s that for the first time enabled the country’s indigenous students to study aspects of their art to levels comparable with those of the longer-established conservatoires of Leipzig, Berlin, Vienna, Paris and London.

Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov was undoubtedly the most gifted Russian composer of his generation – that is to say, those born during the 1860s – and his profound musical aptitude led him to take full advantage of the educational facilities underpinning the burgeoning interest in the arts that grew exponentially in Russia during the second half of the 19th-century.

He was not alone, but Glazunov’s superlative gifts did not lead him initially to a conservatoire. He began musical studies privately with Rimsky-Korsakov (twenty-one years his senior) rather than enter the St Petersburg Academy as just another gifted student. Indeed, it was entirely through the influence of two established older Russian musicians, Mily Balakirev and Rimsky-Korsakov, that Glazunov’s earliest orchestral works were premiered, and it was Balakirev who conducted the premiere of Glazunov’s First Symphony when the composer was just 16 years old. The audience was astounded when a teenage boy in school uniform came on stage to acknowledge the applause. Two years later, the youthful Glazunov was introduced to Liszt in Weimar, who praised the young man’s compositions and general musicianship unreservedly.

Coincidental with Glazunov’s mastery of orchestration – among the important works in his mature output are eight completed symphonies (the Ninth remained unfinished), four concertos and two ballets – are also to be found important chamber music compositions and a relatively extensive output of solo piano works, into which latter genre his two Sonatas are undoubtedly the most significant.

Glazunov had initially been taught the piano from the age of six by his musically-gifted mother and he very soon became an adept pianist. His mature piano Sonatas were written consecutively, appearing in 1900-01, by which time he had been appointed professor at the St Petersburg Conservatoire (he was later elevated to the Directorship of the institution). By the dawn of the twentieth-century, Glazunov’s reputation as one of the undoubted leaders in Russian music was assured, following the deaths of Mussorgsky, Borodin, Tchaikovsky and the Rubinstein brothers during the preceding two decades – and his fame was celebrated not solely within Russia: by that time, Glazunov’s orchestral works had been performed relatively regularly in the United States, and his name was also known and admired across the main centres of European music.

It may be that Glazunov’s greater association with the concept of sonata form, with which his Professorship would naturally have brought him into almost daily contact than otherwise would have been the case, led him to compose his two Sonatas. By 1900, the line of Russian piano sonatas had been firmly established through works by Balakirev, Tchaikovsky, Rubinstein and the first three Sonatas of Scriabin. In 1901, Medtner was to begin his series of – eventually – fourteen piano Sonatas, so Glazunov’s entry into the field was by no means exceptional at that time.

Being composed consecutively, the differences in Glazunov’s Sonatas are fascinating. Their individual tonal bases are exactly opposite: B flat minor and E minor – these keys could not be further apart. It may possibly have been the case that their appearance inspired Igor Stravinsky’s early Sonata in F sharp minor of 1903 through its acceptance of traditional structures – but Stravinsky’s Sonata is in four movements, whereas both of Glazunov’s Sonatas are in three.

Whatever the contemporaneous background to Glazunov’s Sonatas, they are excellent examples of his superlative compositional gifts. Throughout, they constantly reveal elements of genuine organic creativity. The First Sonata, in B flat minor, opens Allegro moderato with an idea that soon becomes subsidiary to what we might consider to be a traditional first subject, but it is the more extended second subject which gradually comes to hold the greater sway, although the opening figure is rarely absent. The relatively brief central development section is intellectually powerful and leads to an impressive recapitulation of the main material before a commensurately consolatory coda.

The Andante middle movement, in the rare key of F sharp major, is fascinating for combining, as Leslie Howard has pointed out, a symmetrical form with variations. It is indeed an original structure in which the variations (not so numbered) are contrasted with selected reminiscences of the opening movement, before a concluding passage balances all together with invention bordering on creative genius.

The Allegro scherzando finale alludes to rondo form, but Glazunov’s originality ensures that the music is far from predictable: the movement’s character may be balletic, and there may indeed be an undisclosed short programme here, but the organic nature of the unfolding material clearly demonstrates the creative skill of a master whose technical demands in this work are not for the faint-hearted.

Glazunov’s First Sonata is dedicated to Rimsky-Korsakov’s wife, Nadezha, herself an accomplished pianist, but the premiere was given by Rachmaninoff’s cousin Alexander Siloti, a pupil of Liszt, in October 1901.

The Second Sonata in E minor is dedicated (in French) ‘To my Master and friend Narcisse Jelenkowski’, Glazunov’s inscription being a tribute to his first piano teacher, with whom he began studying when he was nine years old: Jelenkowski also became the boy’s first teacher of music theory.

The Sonata opens with a sequence of simple phrases, marked Moderato, from which much can (and will) evolve – notably the ‘second subject’, itself a lyrically beautiful theme. However, it is the opening phraseology that impels much of this movement – a sequence of subtle references, perhaps, to those lessons with Jelenkowski? – the texture being at all times pliant and genuinely organic, almost Brahmsian in its organic growth until four spread E minor chords quietly close the music.

Contrasting with the Moderato first movement, Glazunov follows with a Scherzo in C major. In this delightful piece, we are ushered into an Allegretto as if extending to us an invitation to the dance, its central section faster (Poco più mosso), until the initial pulse returns.

The finale’s expression may be considered to be more earth-bound: it begins sturdily, with a theme clearly derived from the opening of the work – a reflection, perhaps, of the composer’s occasionally-admitted acknowledgement of the relatively recently-evolved ‘cyclic’ form, prevalent in the later music of César Franck, a feature also found in various of Glazunov’s symphonic works (and later in the Violin Concerto of 1904).

The Sonata’s finale therefore reinforces the work’s essentially organic nature, which is particularly evinced by a fugal recapitulation. The contrapuntal nature of the music is here far removed from what might be considered a typical Rondo structure, constantly shot through with formal and expressive surprises – and nowhere more so than in the surprising dynamics of the final bars: forte, a sudden surprising piano, then an abrupt fortissimo chord.

Indeed, so unexpected is this startling juxtaposition of dynamics at the very end of the work that we may wonder if it was a private joke (a reminiscence, perhaps?) at Narcisse Jelenkowski’s expense. Whatever the creative impetus, it brings this quite masterly composition to a remarkably effective conclusion.

Glazunov’s Three Miniatures for solo piano Opus 42 were composed eight years earlier. 1893 had proved to be an important year in the 28-year-old composer’s life, both creatively and on a personal level, as it was also to become musically a deeply tragic one. Towards the end of October of that year, it was whilst lunching with a group of friends – a group that included Glazunov – that Tchaikovsky drank the notorious glass of unboiled water during a cholera epidemic in St Petersburg, which act, it was often claimed, led directly to his sudden death a few days later.

However, Glazunov’s three relatively diminutive set of pieces included in Nikolay Medvedev’s recital – Pastorale, Polka and Waltz – had been published some months before the tragic circumstances which led to Tchaikovsky’s death. The tryptich, as a group, whilst reflecting in some ways those virtual salon-type pieces that Tchaikovsky, among many other composers, was so adept at providing for publishers keen to offer to the general public relatively easily playable pieces by the most notable living composers, retain the inherent characteristics of Glazunov’s fluent and directly-expressed creativity. And although in general terms the aesthetic musical content of such items is often of relatively less significance than in their major works, it remains true that the inherent musical character of any composer of worth is equally frequently discernible in those and in similar smaller-scaled genre pieces.

Glazunov, as with many genuine composers, certainly knew the wider commercial, as well as aesthetic, significance of the least important music from his pen. There is an underlying sense of delight in these three brief movements that not only naturally inhabit aspects of the more attractive styles of the period, but also – as later commentators may discern – appear to form a genuine link to the then-burgeoning era of early examples of musical Impressionism and of the contemporaneous ballet theatre scene heard in Russian music towards the end of the nineteenth-century – and which Stravinsky was so soon to embrace.

Robert Matthew-Walker © 2022

Track Listing

- I. Allegro moderato

- II. Andante

- III. Finale. Allegro scerzando

- I. Pastorale. Allegretto

- II. Polka. Allegro

- III. Valse. Allegretto

- I. Moderato – Poco più mosso

- II. Scherzo. Allegretto

- III. Finale. Allegro Moderato

Op. 74: Piano Sonata No. 1 in B♭ minor (1901)

Op. 42: Three Miniatures for piano (1893)

Op. 75: Piano Sonata No. 2 in E minor (1901)