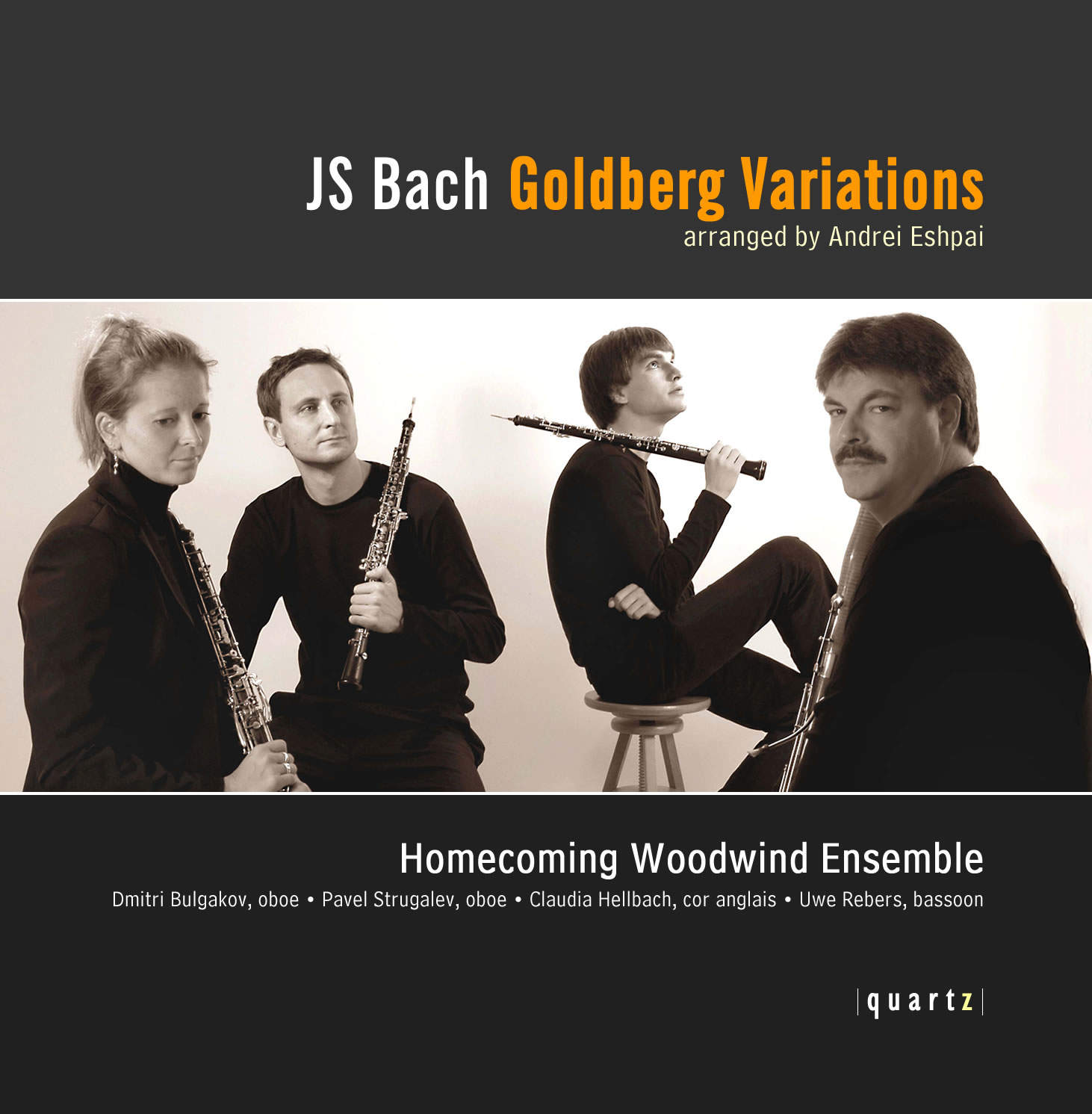

JS Bach – Goldberg Variations

Price range: £4.99 through £11.99

JS Bach – Goldberg Variations

Arranged by Andrei Eshpai

Dmitri Bulgakov, oboe

Pavel Strugalev, oboe

Claudia Hellbach, cor anglais

Uwe Rebers, bassoon

The world premiere recording of Andrei Eshpai’s specially commissioned arrangement of Bach’s much-loved Goldberg Variations performed by one of the world’s most notable young wind ensembles.

About This Recording

J. S. Bach’s apparently infinite resourcefulness of invention, as manifested by his enormously prolific output, is, perhaps, best summarised by one work: The Goldberg Variations. Within this one, self-contained work is displayed Bach’s seemingly endless stream of ideas, his extraordinary ability to weave intricate patterns around the simplest of materials, an ability that would be purely ostentatious were the results not so tastefully and perfectly executed. It comes as no surprise, then, that the richness of this material still has a hugely enduring appeal for performers, composers and listeners alike.

One such performer is oboist Dmitri Bulgakov, who, like so many others, developed something amounting to obsession with this work on hearing it in one of the famous recordings by pianist Glenn Gould. Bulgakov became convinced of the capacity for the keyboard original to be arranged for a homogeneous quartet featuring the oboe. This idea began to take shape when fellow-oboist Pavel Strugalev suggested composer Andrei Eshpai. Eshpai, a renowned master of orchestration, had, amongst many other genres, written numerous concertos, and Strugalev had been one of the first to perform his Oboe Concerto. When Eshpai was approached with this proposal he readily agreed, and the whole concept came to fruition in the form in which we hear it on this disc.

Eshpai’s arrangement of the Goldberg Variations was first performed at the Rachmaninov Hall of the Moscow Conservatory, where Eshpai had studied years before with, among others, Khachaturian. The date of the concert was 20 November, 2005, a year that represented an exceptional conjunction of dates: the 320th anniversary of Bach’s birth, Eshpai’s own 80th birthday, and 50 years since Gould released his first recording of the work. The concert was dedicated to all three anniversaries.

When he was approached with the idea of arranging Bach’s work, Eshpai was already familiar both with handling the music of another composer, and with the technique of variation itself. In 1956, the year in which he finished postgraduate study at the Moscow Conservatory, Eshpai wrote his Variations on a Theme by Glinka for piano. A decade later he wrote both piano and orchestral versions of his Variations on a Theme of Symphony No. 16 by Nikolai Miaskovsky – who had been another of his teachers at the Conservatory. In the case of the Goldberg Variations, however, Eshpai has allowed Bach’s music to breathe through his arrangement without attempting to add further layers of invention to the original. Unlike, for instance, the arrangement of Bizet’s Carmen Suite by Rodion Shchedrin (also taught at the Conservatory under Miaskovsky), in which Shchedrin’s own musical heritage is explicitly articulated, dramatically altering the sound of Bizet’s score, Eshpai does not imprint his own musical character on the Goldberg Variations. Indeed, when asked on stage to receive the applause at the work’s premiere, Eshpai raised his hand to heaven, as though to direct all the praise towards Bach.

For an arrangement to succeed in breathing fresh life into an old work, while simultaneously showing reverence for the character of that work, the choice of instruments is crucial. Bulgakov’s instinct that the Goldberg Variations would adapt well to the sonority of the oboe was well founded; he suggested that in addition to two oboes, the cor anglais and bassoon should be used, which allowed Eshpai to span the range of pitches in Bach’s original. The combination of four double-reed instruments – as opposed to contrasting woodwind timbres, for instance – creates a unified texture, a very fitting equivalent to the evenness of tone one hears on a keyboard instrument. It does, of course, require a feat of stamina from the woodwind players performing this arrangement to sustain Bach’s intricate, often long-breathed phrases with the apparent effortlessness that the nature of the music requires. But it is a feat worthy of the work’s ambitious scale, and one that it must give great satisfaction to accomplish.

The Goldberg Variations are based upon an exquisite opening Aria, from Bach’s second book of pieces for Anna Magdalena Bach, though it is not the melody from this that is varied, as one might expect, but the bass-line and its harmonic implications, as in a passacaglia. The original melody, then, may only be heard or rather, imagined by association, as each variation is essentially motivically self-contained; Bach issues each with fresh thematic material and proceeds to elaborate upon those ideas.

The first variation might be expected to follow the theme with a certain respectful politeness, but instead it halts the tranquillity of the preceding Aria with surprising energy. Variation Two is a more moderate composite of these qualities, and Variation Three is notable as the first of several canons, which are essential in the work’s larger structure, appearing at regular intervals. Variation 4 combines a rustic temperament with the underlying sophistication of its counterpoint.

Thus, within the space of only a few variations, Bach prepares the listener for the astoundingly wide-ranging nature of the music to come. The technique of variation can result in music that is in reality rather repetitious and, ironically, not possessing a great deal of variety. Yet in Bach’s monumental realisation of the form, perhaps only matched by Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations, true variation is achieved.

For instance, the third section of the work is rounded off in G minor by Variation 15, one of the structural canons. The next section begins with an entirely different genre: Variation 16 is an “overture” in the French style with a fugal conclusion. The fifth section begins with the second G minor canon, Variation 21, and is concluded by the third G minor variation, 25, which is further structurally significant in that its introspective character serves as a kind of breathing space, enabling the listener to digest the preceding multiplicity of characters before the final segment, Variations 26-30, begins with renewed vigour.

For Variation 30 Bach reserved a particularly distinctive movement: a “Quodlibet” (“As you please”) based on popular songs of the time. Bach’s first biographer Johann Nikolaus Forkel (1749-1818) recorded that Bach’s family reunions featured the performance of chorales punctuated by irreverent insertions of popular songs, reducing both performers and listeners to helpless laughter. This Quodlibet, then, seems to puncture any preceding gravity, Bach apparently dismissing his previous ingenuity with a good-humoured throwaway gesture. Yet with the final return of the Aria the work is brought full circle, as though prepared to begin all over again.

And it is this timeless quality that lends itself to the story – possibly apocryphal, though it appears in Forkel’s biography of Bach – that lies behind the composition of the Goldberg Variations. When Count Kaiserling, former Russian ambassador to the electoral court of Saxony, was residing in Leipzig, his entourage included the musician Johann Gottlieb Goldberg, who sometimes studied with Bach. The Count suffered ill health, causing bouts of insomnia that would be soothed by Goldberg’s playing. On one occasion this scenario was mentioned to Bach, who set about producing a set of keyboard variations for Goldberg to play to the sleepless Count. The Count was enchanted by the work, and rewarded Bach handsomely. Whether this account is entirely true or not, it does further conjure up the sense that the Goldberg Variations, like Bach’s inspiration itself, might almost be endless; fed by a well of invention that never dries up, they could yet be played on into the night, and into eternity.

© Joanna Wyld, 2006

Track Listing

-

J.S. Bach

- Goldberg Variations: Aria

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 1

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 2

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 3. Canone all Unisono

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 4

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 5

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 6. Canone alla Seconda

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 7

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 8

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 9. Canone alla Terza

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 10. Fughetta

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 11

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 12. Canone alla Quarta

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 13

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 14

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 15. Canone alla Quinta

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 16. Ouverture

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 17

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 18. Canone alla sesta

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 19

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 20

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 21. Canone alla Settima

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 22. Alla breve

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 23

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 24. Canone all Ottava

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 25

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 26

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 27. Canone alla Nona

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 28

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 29

- Goldberg Variations: Variation 30. Quodlibet

- Goldberg Variations: Aria da capo