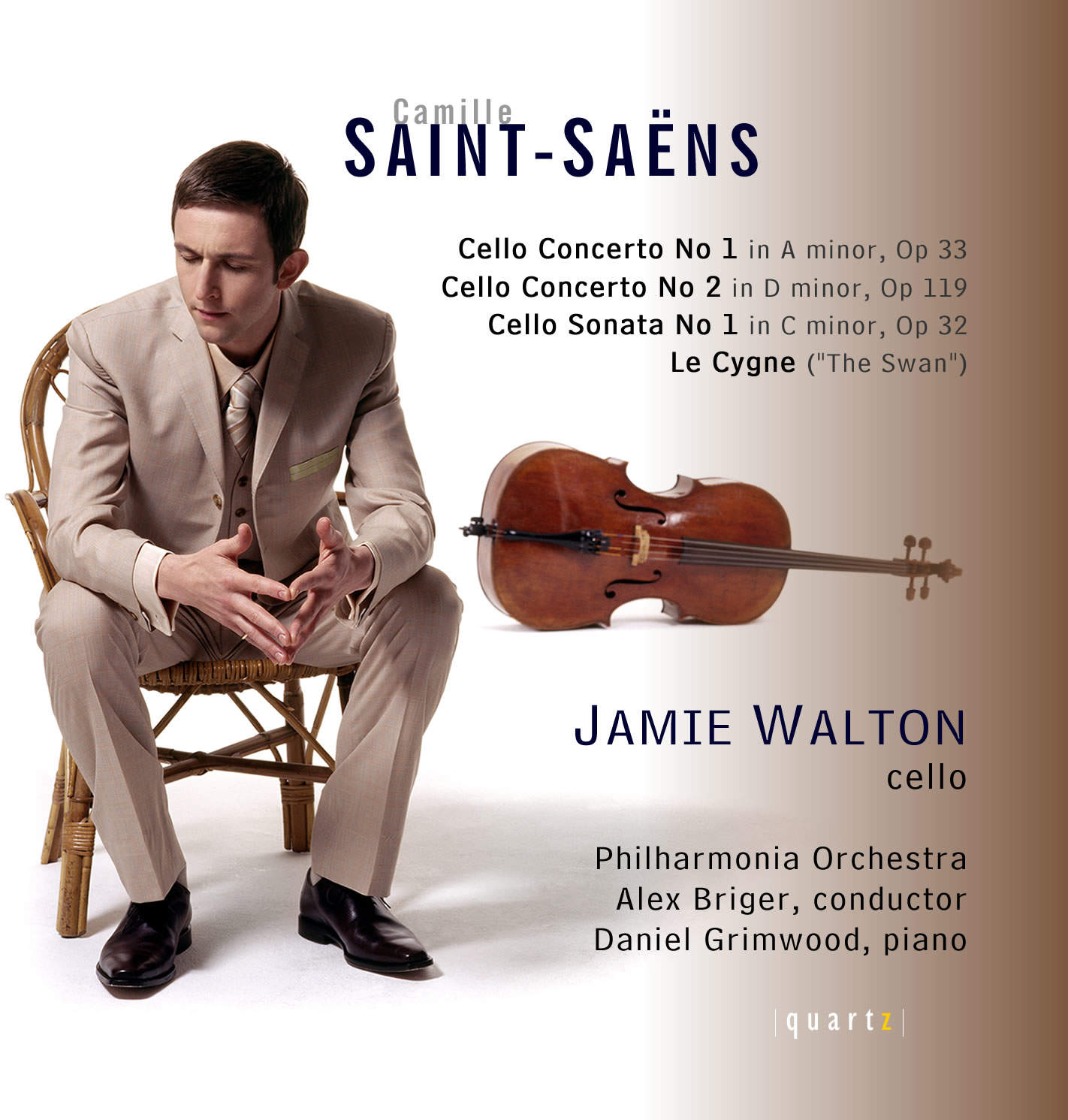

Saint-Saens – Cello Works

Price range: £4.99 through £11.99

Cello Concerto No 1 in A minor, Op 33

Cello Concerto No 2 in D minor, Op 119

Cello Sonata No 1 in C minor, Op 32

Le Cygne (“The Swan”)

Jamie Walton, Cello

Philharmonia Orchestra

Alex Briger, Conductor

Daniel Grimwood, Piano

This wonderful new album from the rising star of the cello world is both a showcase for Jamie Walton’s extraordinary talent and, at the same time, a demonstration of the breadth and beauty of Saint-Saens’ writing for this instrument.

About This Recording

CONCERTO NO.1 in A MINOR OP.33

Camille Saint-Saens was a child prodigy of the first order, composing aged 4 with a precocity worthy of Mozart. At ten, he had memorised all 32 Beethoven sonatas at the same time as he was already dazzling Parisian audiences with his brilliance as a virtuoso pianist. Liszt was later to hail him as the greatest living organist. Considering that he travelled all over the world, writing journals and treatises (on Roman theatres), plays, poetry, essays on philosophy, botany, astronomy and the occult, we can only regret that the current trend is to view Saint-Saens as superficial and lacking in profundity.

“I ran after the chimera of purity, of style and perfection of form”. From that statement a portrait emerges of the composer’s leaning towards polished expression, an elegant sense of line, and lucid clarity. The genius of Saint-Saens was, I feel, to write music with a classical discipline in order to restrain an overtly romantic interpretation, which must be sincere, never indulgent.

The concerto No.1 in A minor (1872) was an immediate success and it is easy to see how its popularity has been maintained. From the beginning, it reveals a composer at the height of his melodic and dramatic powers. Shostokovich went as far to hail this masterpiece as his favourite concerto. One can see why. Saint-Saens immediately gives lie to the myth surrounding his even temperament by presenting a passionate opening passage for the soloist, restlessly conversing with the orchestra until the cello introduces a second, exquisite, almost Schumannesque theme.

The three movements themselves are bridged without a break, adding to the graceful sense of line. So, after the tempestuous first movement, we are led seamlessly into a contrasting minuet, with muted strings and elegant waltzes. The developments that follow convey the epitome of romantic spirit, glorious for both cello and orchestra, launching into a vigorous molto allegro like a whirlwind unleashed. A buoyant a major coda brings this consummate concerto to a dazzling finish.

SONATA IN C MINOR FOR CELLO AND PIANO, Op.32

Composed in the difficult year following France’s humiliating defeat in the Franco-Prussian War and allegedly inspired by the death of a great-aunt to whom Saint-Saens was very close, the Op. 32 sonata is an uncharacteristically dark work which portrays a moodier side to this most effervescent of composers. Throughout, the musical argument is concise, even terse, with the piano spitting irate passage work in the outer movements and the more reticent cello part focused almost exclusively on the lower register.

Although Op. 32’s physiognomy may, at first glance, appear conventional, it displays quite a few unorthodox features – as so often in Saint-Saens, outward simplicity conceals an extremely lucid technical sophistication: The exposition of the strict sonata-form 1st movement concludes, unusually, in Db major- a rise of a semitone above the home key of C minor and, therefore, an inversion of the 2nd and 3rd notes of the principal theme (C – B-natural). The key of Db major will be repeated in the central section of the ternary 2nd movement (in a passage whose meandering, at times bizarre, harmonies and rippling piano figurations anticipate his late style and also pre-echo Faure) and the rising or falling tone or semitone will define each and every motive in the entire sonata.

When Jamie and I started learning this engaging piece we were both convinced that Saint-Saens must have been conversant with Schubert’s C minor piano sonata D958. Although much of Schubert’s instrumental music was unknown at the time it is entirely possible that Saint-Saens, with his encyclopaedic knowledge and imposing intellect, would have known at least some of Schubert’s sonatas.

For me, this sonata evokes the legend of Giselle, which was very much part of the European collective subconscious at that time with its cocktail of the romantic, the tragic, the elegant and the macabre.

CAMILLE SAINT-SAENS – LE CYGNE (Andantino grazioso)

“Le Carnaval des animaux” was deliberately not published in his lifetime. A startlingly original but fascinating work, Saint-Saens felt that he could not risk tarnishing an already fragile reputation further. However, “Le Cygne”, (movement No.13), was permitted for publication by the composer and it is evident why; for all its simplicity, “Le Cygne” has flourished into one of the most popular, recognisable and enchanting works for cello (and two pianos).

Daniel and I, having become accustomed to Adagio renditions, discovered on inspection that Saint-Saens does in fact suggest an Andantino grazioso, thus discarding the temptation to wallow and replacing it with a more fluid interpretation. This may cause raised eyebrows! Complying with a composer’s wishes must be a prerequisite for an authentic performance.

CONCERTO NO.2 IN D MINOR, Op.119

“Trop difficile” Saint-Saens

Few concertos are deemed too difficult – those of Tchaikovsky, Prokofieff and Rachmaninoff, for example, have all found soloists to do them justice in due course. But the D minor concerto (1902)calls for its own, special champion. One critic acutely observed;: “such acrobatics are demanded of the player that the solo part is written on two staves. One listens with something of the apprehension felt on watching a death-defying trapeze artist.” AT the same time, through sparse yet masterly orchestration, we also experience moments of clarity, serenity and poignancy while remaining oblivious to the composer’s excessive demands on the performer.

The composition on two staves, much like a piano score, presents the soloist with a fiendishly difficult and daring work that oscillates between the audaciously novel and the conformist, for it doesn’t sound particularly pyrotechnical or unplayable. Its lyricism conceals the compositional impracticalities.

Incorporating colours and textures that depict a range of styles and idioms, from Baroque flourish to Mahlerian lusciousness, here is an unjustly neglected work. Its defiant opening is echoed by a declamatory entrance from the cello, which evolves into a passage of expressive double-stopping, applied thematically/obstinately (!) throughout the concerto. The arduous physical demands of this writing only adds to the gravity of the music. Saint-Saens was seemingly aware that his music was at the mercy of the interpreter and we can see how in order to prevent independent liberties, he has placed a restriction on those who don’t wish to take his music seriously enough! Unconventional yet again, this first of two movements that began so dynamically, winds down into a twilight passage of exquisite calm.

The Finale, bristling with virtuoso brilliance, begins with scintillating effervescence; rather like a ballet dancer, the soloist is called upon to execute passages with dexterity and aplomb! Rapidly and relentlessly, we arrive at the oratorical cadenza with its curious and original recitative and pizzicato interlude accompaniment. A spectacular coda brings this intriguing and rather extraordinary concerto to an inspired finish.

Track Listing

-

Camille Saint-Saens

- Concerto No 1 in A minor (i) Allegro non troppo

- Concerto No 1 in A minor (ii) Allegretto con moto

- Concerto no 1 in A minor (iii) Tempo primo

- Sonata No 1 in C minor (i) Allegro

- Sonata No 1 in C minor (ii) Andante tranquillo sostenuto

- Sonata No 1 in C minor (iii) Allegro moderato

- Le Cygne (from Le Carnaval des Animaux)

- Concerto No 2 in D minor (i) Allegro moderato e maestoso; Andante sostenuto

- Concerto No 2 in D minor (ii) Allegro non troppo; Cadenza; Tempo 1; Molto allegro