Schumann: Works for Piano

Price range: £7.99 through £16.99

In the suite of twelve miniatures published as Papillons in April 1832, Schumann paid simultaneous tribute to his two idols, Jean-Paul (alias Johann Paul Richter) and Franz Schubert.

Fantasie in C major – arguably Schumann’s piano masterpiece – we move forward to the summer of 1836, when Robert and Clara were forbidden by her implacable father to meet or correspond. That June Schumann sublimated his despair at their enforced separation in a movement titled Ruines. Fantaisie…. In the autumn he added two more movements, Trophies and Palms, to create what he termed a ‘Grand Sonata for the Pianoforte for Beethoven’s Monument…’ – a reference to Liszt’s project to raise funds for a Beethoven monument in Bonn. Revising the music for publication in 1838 – by which time he and Clara were secretly engaged – Schumann wrote to her that ‘the first movement is more impassioned than anything I have ever written – a deep lament for you’

Resorting, not for the only time, to nineteenth-century sexual stereotyping, Schumann described the Arabeske and the contemporary Blumenstück as ‘delicate – suitable for ladies’. Both pieces seem to have been written as a riposte to criticisms, not least from Clara, that his piano music was too abstruse and demanding – ‘sheer revellings in strangeness’, as one critic put it. Faschingsschwank aus Wien (Carnival Jest from Vienna)is in effect an eccentric – and pianistically challenging – five-movement sonata in B flat. Indeed, Schumann variously dubbed it‘a grand Romantic sonata’ and ‘a romantic showpiece’.

About This Recording

Schubert is still “my only Schubert”, especially as he has everything in common with “my only Jean-Paul”. When I play Schubert I feel as if I were reading a novel of Jean-Paul

set to music.’ In November 1828 the eighteen-year-old Robert Schumann had sobbed all night at the news of Schubert’s death. A year later, in a letter to his piano teacher and future father-in-law Friedrich Wieck, he identified his twin idols, one musical, the other literary. Little read today, Jean-Paul (alias Johann Paul Richter) was a purveyor of tangled, antic fantasies, whose prose style was aptly dubbed ‘a wild complicated Arabesque’ by the admiring Thomas Carlyle. The young Schumann eagerly devoured his novels, noting in his diary, ‘If everyone read Jean-Paul they would be better, if a lot more miserable.’

In the suite of twelve miniatures published as Papillons in April 1832, Schumann paid simultaneous tribute to his two idols. His avowed ‘Bible’ among Jean-Paul’s novels was Flegeljahre (translated by Carlyle as ‘Years of Wild Oats’), whose protagonists, the twins Walt and Vult Harnisch – one a dreamer, the other an impulsive extrovert – were the model for his own fictional personae, Eusebius and Florestan. In a letter to the poet Ludwig Rellstab, Schumann revealed the specific inspiration behind Papillons. ‘You remember the last scene in Flegeljahre – masked ball – Walt – Vult – masks – Wina – dancing – the exchange of masks – confessions – anger – revelation – rushing away – the closing dream and then the departing brother. I often turned to the last page, for the ending seemed to me merely a new beginning – almost unconsciously I was at the piano, and so one Papillon after another came into being.’

Schumann’s title for the suite reveals his love of punning and ciphers, shared with Jean-Paul, whose novel is full of butterfly imagery. The German for masked ball is Larventanz, with ‘Larve’ meaning both a mask and a larva. The twelve miniatures had indeed undergone various metamorphoses, like larvae, before emerging as fully fledged butterflies.

In transmuting the masked ball into music, Schumann also evoked the spirit of Schubert’s piano waltzes. When the composer’s friends heard him play the original versions of some of the dances, they were deceived into thinking they were actually by Schubert. The opening waltz, with its elegant élan, and the stomping Ländler of No.8 makes the point.

Schumann’s own annotated copy of Flegeljahre relates the episodes in the masked ball to individual numbers in Papillons. Thus No.2, a capricious Prestissimo, evokes the ‘aurora borealis sky full of crossing zig-zagging figures’, while the clunking, lumpen octaves of No.3 conjure the surreal antics of a giant boot, ‘sliding around, dressed in itself’. Amid the swirling animation, the chromatically wistful No.5, and the ethereal valse triste of No.7 appear as oases of reflection.

The penultimate dance (11) contrasts a swaggering polonaise and fragile, diaphonous lyricism, while the finale opens with the time-honoured Grossvatertanz (‘Grandfathers’ Dance’), which is then counterpointed with the opening waltz: a musical illustration of Schumann’s remark that ‘the ending seemed to me merely a new beginning’. (A few years later Schumann used this Grossvatertanz, traditionally danced at the conclusion of a ball, to mock the philistines at the end of Carnaval.) At the close, the clock chimes six, the Grossvatertanz dissolves in fragments and the vision fades, magically and enigmatically.

With the Fantasie in C major – arguably Schumann’s piano masterpiece – we move forward to the summer of 1836, when Robert and Clara were forbidden by her implacable father to meet or correspond. That June, Schumann sublimated his despair at their enforced separation in a movement titled Ruines. Fantaisie…. In the autumn he added two more movements, Trophies and Palms, to create what he termed a ‘Grand Sonata for the Pianoforte for Beethoven’s Monument…’ – a reference to Liszt’s project to raise funds for a Beethoven monument in Bonn.

Revising the music for publication in 1838 – by which time he and Clara were secretly engaged – Schumann wrote to her that ‘the first movement is more impassioned than anything I have ever written – a deep lament for you’. By that stage the second and

third movements were called Triumphal Arch and Constellation, and the ‘Grand Sonata’ had become a Fantasie. When the Fantasie in C major appeared in print in 1839, with a dedication to Liszt, Schumann dropped the titles in favour of an apparently cryptic quotation from the Romantic poet-philosopher Friedrich Schlegel: ‘Through all the sounds in earth’s motley dream, one soft note echoes for the one who listens in secret’.

‘Are not you really the “note” in the motto?’ wrote Robert to Clara in a letter of June 1839. ‘I almost believe you are.’

Living up to its billing ‘fantastic and passionate throughout’, the first movement grows from the ‘Clara motto’ of five descending notes, heard in the opening bars. Also threaded through the movement are veiled, sometimes disturbed, references to the last song in Beethoven’s An die ferne Geliebte, which finally sounds explicitly in the coda: at once a tender avowal to Schumann’s own ‘distant beloved’, and a reminder that Schumann had also conceived the Fantasie as a homage to Beethoven.

Clara described the bold, marchlike second movement as ‘a victory march of warriors returning from battle’. Schumann here augments the orchestral weight of sound with full, spread chords that fractionally anticipate the main beat. Clara’s motto reappears both in the main section (in canonic imitation) and in the more relaxed central Trio, where, typically of Schumann, the melody is often half-concealed in an inner part. After two such highly charged movements the finale, marked ‘slowly and softly throughout’, exudes a profound spiritual peace. The Clara allusions here are legion, beginning with the motto (sounded in the bass in bar five), and continuing with an unmistakable reference to Schubert’s song ‘Die Gebüsche’ (‘The Bushes’), which contains the Schlegel lines quoted above. A beautiful dip from C major to A flat introduces yet another Clara-related theme. Schumann abandoned his original idea of ending with the An die ferne Geliebte song, closing instead with a reference to the A flat theme before the music subsides into the beatific calm of C major.

Determined to shore up his finances before his anticipated marriage to Clara, Schumann spent the autumn and winter of 1838-39 in Vienna, where he hoped to establish himself both as a composer and as the publisher of his journal, the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. Hope quickly turned to disillusionment in a city he found too full of gossip and triviality, with a Philistine underside to its famed Gemütlichkeit. Yet his Viennese stay was fruitful in other ways. Early in 1839 he visited Schubert’s brother Ferdinand and delightedly discovered a huge pile of unpublished manuscripts, including the ‘Great’ C major Symphony. In Vienna, too, Schumann completed the Arabeske, Op.18, and the first four movements of the Faschingsschwank aus Wien, adding the finale after his return to Leipzig in spring 1839.

Resorting, not for the only time, to nineteenth-century sexual stereotyping, Schumann described the Arabeske and the contemporary Blumenstück as ‘delicate – suitable for ladies’. Both pieces seem to have been written as a riposte to criticisms, not least from Clara, that his piano music was too abstruse and demanding – ‘sheer revellings in strangeness’, as one critic put it. On one level the Arabeske is a guileless rondo, with a gracefully rippling refrain and two minor-keyed episodes, the second of which alludes to the refrain, but Schumann being Schumann, the music is replete with poetic subtleties: in the way the first episode gradually fades into reverie, or in the tenderly musing coda, whose dissolving arpeggio texture anticipates the postlude of Dichterliebe.

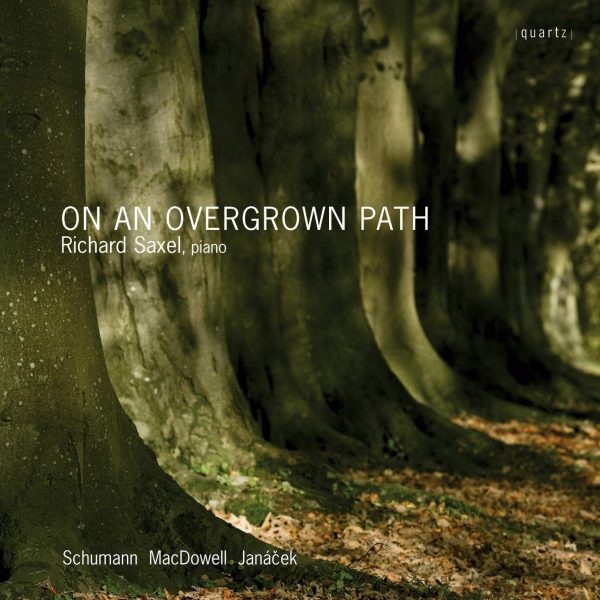

booklet-paginated:cover

Dedicated to the Belgian pianist and Schumann admirer Simonin de Sire, Faschingsschwank aus Wien (Carnival Jest from Vienna) is in effect an eccentric – and pianistically challenging – five-movement sonata in B flat. Indeed, Schumann variously dubbed it ‘a grand Romantic sonata’ and ‘a romantic showpiece’. As to the

‘jest’ of the title, this surely refers to the use of the ‘Marseillaise’, then banned in Metternich’s ultra-conservative Vienna, in the rondo-like opening movement. Transformed into waltz time, the French anthem is first hinted at after a pounding

F sharp major episode that sounds like a Schubertian dance (shades here of the stomping No.8 in Papillons), then emerges blatantly, in ‘brassy’ scoring. Either side of the ‘Marseillaise’ there are also echoes of the Grossvatertanz that had played such a crucial role in Papillons and Carnaval.

The extrovert Florestan yields to Eusebius the dreamer in the Romanze second movement. Its tonally ambiguous opening (a Schumann trademark) outlines the descending ‘Clara motto’ that permeates the first movement of the C major Fantasie. With a nod to Mendelssohn’s fairy music, the capricious, faintly folksy Scherzino trades on quickfire dialogues between different registers and nonchalant shifts to distant keys.

The Intermezzo fourth movement is an impassioned, harmonically restless song without words, buoyed by a constant swirl of triplets and constantly evading the home key of E flat minor. Perhaps to vindicate his description of the Faschingsschwank as a sonata, Schumann’s finale is a coruscating movement in more-or-less orthodox sonata form. It begins like an updated Baroque toccata, alludes teasingly to the Scherzino in the central development, and ends with a barnstorming reference to the work’s opening bars.

© Richard Wigmore

Track Listing

- Arabeske in C major, Op. 18 Fantasie in C major, Op. 17

- I. Durchaus phantastisch und leidenschaftlich vorzutragen

- II. Mässig: Durchaus energisch

- III. Langsam getragen: Durchweg leise zu halten Papillons, Op. 2

- Introduzione – I -

- II. Prestissimo

- III. -

- IV. Presto

- V. -

- VI -

- VII. Semplice

- VIII. -

- IX: Prestissimo

- X. Vivo

- XI. -

- XII. Finale Faschingsschwank aus Wien, Op. 26

- I. Allegro: Sehr lebhaft

- II. Romanze

- III. Scherzino

- IV. Intermezzo

- V. Finale