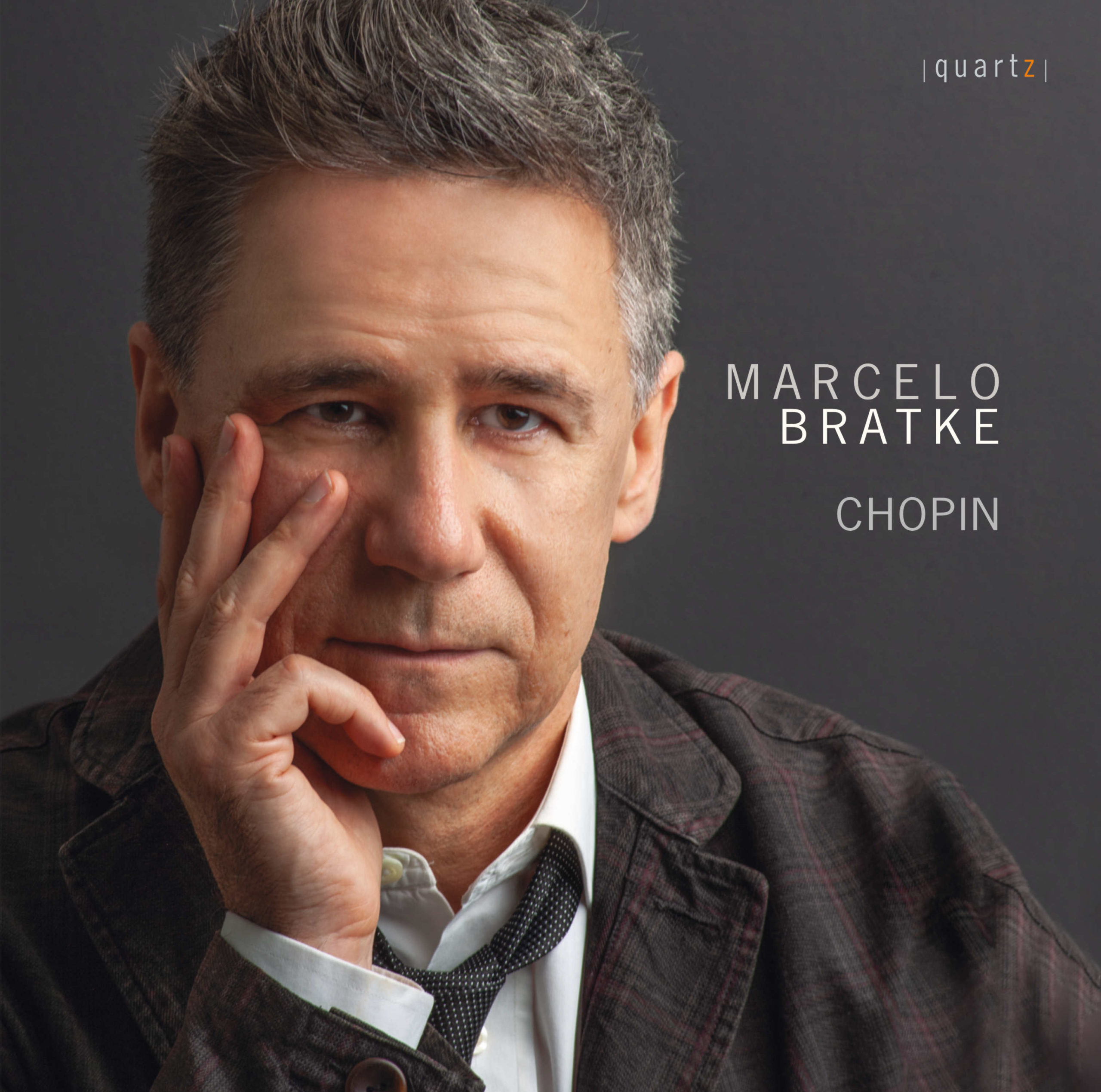

Chopin: Piano Music

Price range: £7.99 through £14.99

The cycle of Chopin’s Preludes Op. 28 and the 2 posthumous preludes No. 25 in C Sharp Minor Op. 45 and No. 26 in A-Flat Major B. 86 are based on contrasts. Contrasts of expression, dynamics, rhythm and colour, revealing romanticism in its full element of emotional instability, but at the same time the cycle reveals a coherence which comes from the fact that the preludes have been built around the twenty-four keys, twelve major and twelve minor, chasing the ideas of fullness which are present in Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, that inspired Chopin during that winter. The fact that his musical idols were Bach and Mozart perhaps explains his classic quality ever-present in his ultra-Romantic music. Chopin’s first Prelude in C Major, for example, clearly mirrors the C Major Prelude of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier and on the other hand Chopin’s counterpoint, which is so Bachian, revealing sometimes elements that bring back Mozart and his way of designing the melodic lines of his operas where the sopranos sing melodies as if they were being transported by the wind.

About This Recording

My first encounter with Chopin was also my first encounter with the piano.

It all started on a Saturday afternoon in São Paulo when, visiting my father’s house, he surprised me by playing on an old Pleyel piano, a Prelude by Frederic Chopin – Prelude No.4 in E minor Op.28. I was 14 years old and was so impressed by the music that I spent the entire afternoon at the piano trying to memorise those passages by ear until I suddenly managed to play the entire piece by memory without ever touching a keyboard before in my life.

Rubinstein’s recording of Chopin’s 24 Preludes plunged me into his universe of sound, and the stories told by my first piano teacher Zelia Deri, triggered my fantasy immediately. Stories full of mystery as the one in Mallorca where Chopin and his lover, George Sand, spent a turbulent winter in 1838 in adjacent rooms of an old monastery in Valldemossa where Chopin composed his Preludes, a collection of piano pieces that contain, like no other, the essence of human imagination transformed into music.

The cycle of his Preludes Op.28 and the two posthumous preludes No.25 in C sharp minor Op.45 and No.26 in A flat major B.86 are based on contrasts. Contrasts of expression, dynamics, rhythm and colour, revealing romanticism in its full element of emotional instability, but at the same time the cycle reveals a coherence which comes from the fact that the preludes have been built around the twenty-four keys, twelve major and twelve minor, chasing the ideas of fullness which are present in Bach’s Well Tempered Clavier, that inspired Chopin during that winter in Mallorca.

The fact that his musical idols were Bach and Mozart perhaps explains his classic quality ever present in his ultra-Romantic music. Chopin’s first Prelude in C major, for example, clearly mirrors the C major Prelude of Bach’s Well Tempered Clavier and on the other hand Chopin’s counterpoint, which is so Bachian, reveals sometimes elements that bring back Mozart and his way of designing the melodic lines of his operas where the sopranos sing melodies as if they were being transported by the wind.

Warsaw in March 1810. He was acclaimed in Poland as a child prodigy. Echoes of his talent crossed the Polish borders and impressed Robert Schumann, who wrote in a German newspaper: “Take off your hats, gentlemen! A genius!” At the age of 20 Chopin leaves Poland forever. One month after his departure to Vienna, the November Uprising broke out in Poland and then came the occupation of the country by the army of the Russian Empire. In September 1831, Chopin arrived in Paris.

Chopin brought the DNA of Poland to his music. He composed his four Mazurkas Op.17 between 1832 and 1833 in Paris where his debut at Salle Pleyel made him into a celebrity. He had a completely different way of playing the piano compared with other pianists. “An impeccable legato, a beautiful cantabile and an unforgettable rubato” described by an amateur pianist of his time but Chopin only performed just over 30 concerts during his entire life. “I’m not made for concerts. The crowd frightens me, I’m transfixed by those curious, speechless looks and those foreign faces. In music, simplicity is the ultimate achievement.” he said.

Although Chopin hoped he could come back to Poland when the political system might have changed, his hope never materialised. His Mazurkas Op.17 reflect this homeland nostalgia as is revealed in its chromatic harmonies of introspective moods which brought a new sound vocabulary to the piano with a range of colours that no one before him had imagined.

Chopin’s Fantasy Impromptu in C sharp minor Op.posth.66 was written in 1834, around the same time he wrote the Four Mazurkas Op.17. It was published posthumously and much speculation has been raised as to why Chopin did not want this work published. In 1960, Arthur Rubinstein acquired, at an auction in Paris, the “Album of the Baroness d’Este” containing Chopin’s Fantasy Impromptu and discovered many harmonic improvements added by Chopin in 1835. The album also contained the following inscription in Chopin’s own handwriting: “Compounded for the Baroness d’Este by Frédéric Chopin” which, according to Rubinstein, revealed that the composer probably sold the work to the Baroness and was not supposed to publish it.

The Berceuse in D flat major Op.57 is one of Chopin’s most extraordinary works. It dates from his late years (1844) and was published the following year. This short composition is a lyrical masterpiece in which Chopin’s artistry is in its fullest.

The origin of the Berceuse is probably linked to Chopin’s enchantment with Louise, the eighteen-month-old daughter of his friend, the singer Pauline Viardot. “Chopin adores her and spends his time kissing her little hands”, wrote George Sand in a letter. The moments Chopin spent with Louise may well have inspired him to write his lullaby.

The Berceuse is based on a four-bar theme, followed by a series of sixteen variations. Throughout the piece, the right hand is accompanied by the left hand that brings a formula, that almost always sounds the same, with a bass and some chords revealing a static and monotonous atmosphere as if time were suspended. However, the right hand, with its successive variations and its inexhaustible inventiveness, prevents the listener from feeling any kind of monotony, which gives the work a storyteller character consistent with the meaning of a real lullaby.

One of the characteristics of the Romantic period in music is that a certain “persona” begins to emerge as an important element of the work and the work sometimes merges with its creator. This happens in Chopin’s music where the narrative brings us to a level of intimacy with the composer.

Almost everything that Chopin ever wrote is still played. Chopin influenced the entire last half of the nineteenth century and continues to influence composers even today. From Liszt to Wagner, from Moszkowski to the young Scriabin, or from Ernesto Nazareth to Tom Jobim, Chopin is still alive as a composer without borders in time and space who never left us and will never do so.

—Marcelo Bratke

Track Listing

- Prelude in C major Op.28, No.1

- Prelude in A minor Op.28, No.2

- Prelude in G major Op.28, No.3

- Prelude in E minor Op.28, No.4

- Prelude in D major Op.28, No.5

- Prelude in B minor Op.28, No.6

- Prelude in A major Op.28, No.7

- Prelude in F-sharp minor Op.28, No.8

- Prelude in E major Op.28, No.9

- Prelude in C-sharp minor Op.28, No.10

- Prelude in B major Op.28, No.11

- Prelude in G-sharp minor Op.28, No.12

- Prelude in F-sharp major Op.28, No.13

- Prelude in E-flat minor Op.28, No.14

- Prelude in D-flat major Op.28, No.15

- Prelude in B-flat minor Op.28, No.16

- Prelude in A-flat major Op.28, No.17

- Prelude in F minor Op.28, No.18

- Prelude in E-flat major Op.28, No.19

- Prelude in C minor Op.28, No.20

- Prelude in B-flat major Op.28, No.21

- Prelude in G minor Op.28, No.22

- Prelude in F major Op.28, No.23

- Prelude in D minor Op.28, No.24

- Prelude in C-sharp minor Op.45, No.25

- Prelude in A-flat major B.86 Op.Posth., No.26

- Mazurka No.10 in B-flat major Op.17, No.1

- Mazurka No.11 in E minor Op.17, No.2

- Mazurka No.12 in A-flat major Op.17 No.3

- Mazurka No.13 in A minor Op.17, No.4

- Fantaisie Impromptu in C-sharp minor Op.Posth., 66

- Berceuse D-flat major Op.57