Brahms: Orchestral Works

£7.99 – £16.99

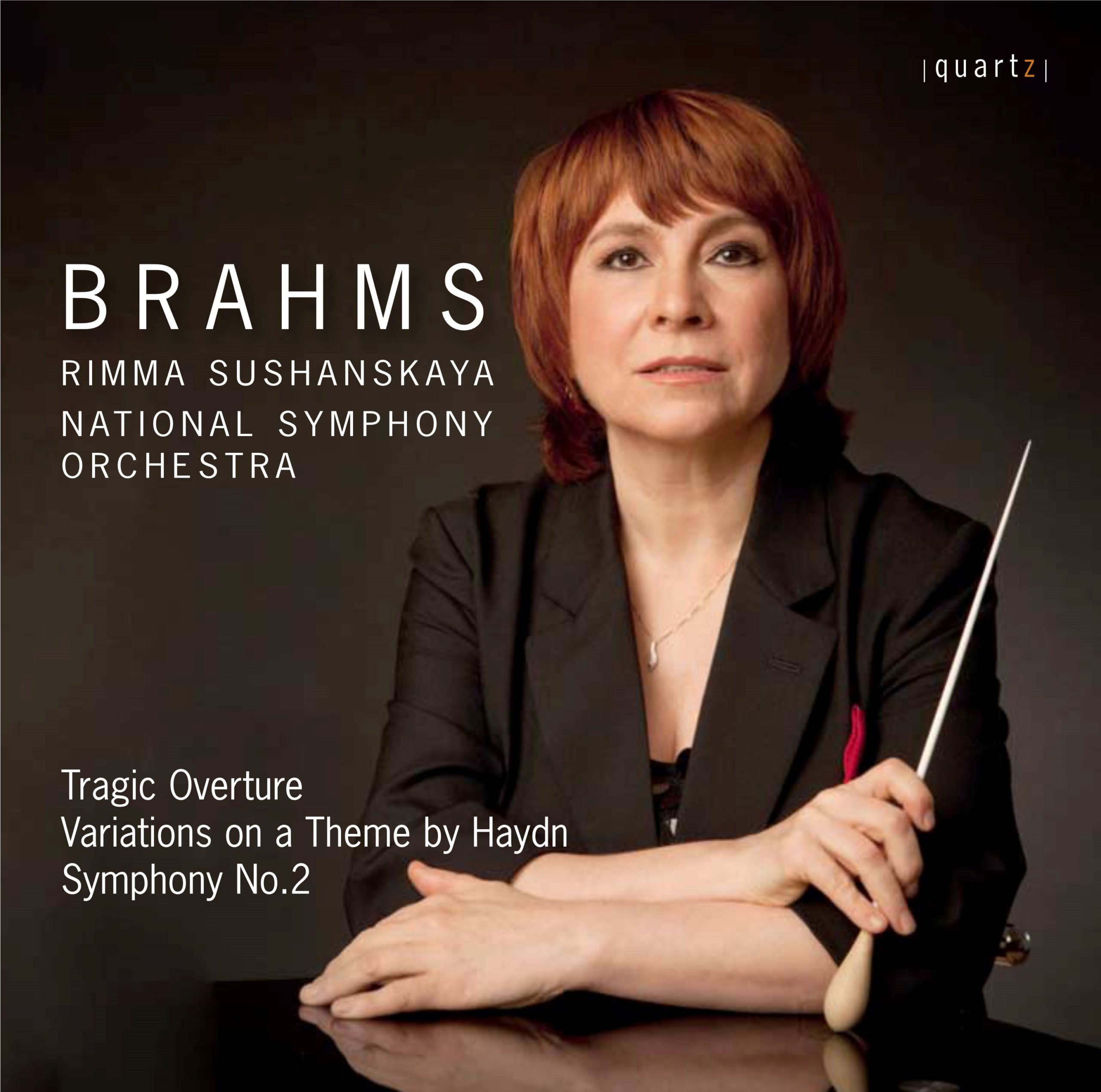

The National Symphony Orchestra is delighted that Rimma Sushanskaya, the distinguished violinist and conductor, has accepted a formal role with the orchestra. Critically acclaimed performances and recordings in recent years have developed a synergy, a shared passion, for music making. This is no more apparent than found in their recent recordings of Beethoven’s5th Symphony and the two Romances for violin, partnering Mathilde Milwidsky as soloist, and an album of Mozart Symphony No.40 and the Elvira Madigan Piano Concerto No.21 in C with John Lenehan. Sushanskaya has found an energy and vision, giving inspiration for the present and a huge sense of eager anticipation for the future. This album of works by Brahms was recorded during the height of COVID restrictions whereby social distancing in studios was a requirement for British orchestras, representing huge challenges for both performers and recording engineers alike. The recording is a tribute to the indefatigable efforts of our conductor, musicians, producer Michael Ponder and sound engineer Adaq Khan and the supportive staff at Henry Wood Hall, all who managed to keep the candle burning for music and musicians when almost all artistic activity fell silent.

About This Recording

The National Symphony Orchestra is delighted that Rimma Sushanskaya, the distinguished violinist and conductor, has accepted a formal role with the orchestra. Critically acclaimed performances and recordings in recent years have developed a synergy, a shared passion, for music making. This is no more apparent than found in their recent recordings of Beethoven’s5th Symphony and the two Romances for violin, partnering Mathilde Milwidsky as soloist, and an album of Mozart Symphony No.40 and the Elvira Madigan Piano Concerto No.21 in C with John Lenehan. Sushanskaya has found an energy and vision, giving inspiration for the present and a huge sense of eager anticipation for the future. This album of works by Brahms was recorded during the height of COVID restrictions whereby social distancing in studios was a requirement for British orchestras, representing huge challenges for both performers and recording engineers alike. The recording is a tribute to the indefatigable efforts of our conductor, musicians, producer Michael Ponder and sound engineer Adaq Khan and the supportive staff at Henry Wood Hall, all who managed to keep the candle burning for music and musicians when almost all artistic activity fell silent.

In considering Brahms’s creative life as a composer, we often find examples where, having begun a work, ideas of a very different nature would occur to him, virtually contemporaneously, leading to the creation of a new piece, frequently in a similar format but almost invariably different in character. This creative characteristic can be found throughout his life, from the early two Serenades for orchestra to his final Sonatas for clarinet.

Perhaps the most remarkable chain of creative circumstances in this vein can be discerned in Brahms’s compositions which followed the Fourth Symphony in E minor. This great work appeared in 1886, and the Symphony is in four- movements, broadly acknowledging traditional formal sonata structures – except for the innovative passacaglia-based last movement. Brahms soon followed the Symphony with a similar four-movement chamber work – his Second Sonata for cello and piano – most intriguingly, we may note that the cello’s opening phrase can be related to the first subject of the Fourth Symphony. Brahms’s next work was another Sonata, for violin and piano – but in three movements; this was followed by another chamber-music work, the third in succession, which combined the violin and cello of the two preceding Sonatas with piano, to form his Third Piano Trio in C minor. Finally, completing this quintet of successive works, Brahms combined the cello and violin of the preceding chamber works as soloists with symphony orchestra in his Double Concerto.

This sequence may well be the most intriguing example of Brahms’s consecutive works inspired (or, at the very least, suggested) by the immediately preceding composition, but the most famous ‘dualism’ in his output are undoubtedly two Overtures, composed in 1879-80: the Academic Festival, Opus 80, and the Tragic Overture, Opus 81.

In character, as their titles suggest, they could not be more different. The Academic Festival Overture arose through the award to Brahms by the University of Breslau of an honorary doctorate. Brahms was flattered by this, as he did not attend university as a young man (nor, indeed, any seat of learning); his response was a brilliant overture based largely on student songs.

But no sooner had the Academic Festival Overture appeared than Brahms followed it with the great – and vastly different in character – Tragic Overture.

Brahms’ Tragic Overture was claimed at one point to have arisen through a frustrated attempt to stage Goethe’s Faust in Vienna, but – whether true or not – Brahms, in this magnificent work, created a symphonic portrait of defiance against adversity, within a genuinely symphonic mould lasting around a quarter of an hour. No overt literary connection is claimed for the Tragic Overture, giving the work – in three broadly continuous sections, subtly related thematically – a powerful sense of organic unity of universal relevance. The manner by which Brahms moulds his dramatic themes, maintaining an overall tragic atmosphere, is the work of a composer of genius – and the final sense of fierce triumph over adversity, through the symphonic nature of the recapitulation, is powerfully impressive.

Brahms’ Variations on a Theme by Haydn (the ‘St Anthony’ Chorale) Opus 56a occupies such a regular position in the international orchestral repertoire today that it may be difficult for us to appreciate how unusual it must have seemed when the work first appeared in 1873.

For Brahms, the concept of writing variations was not a new departure for him. From his Opus 9 (1854), Variations on a Theme of Robert Schumann (dedicated to Clara Schumann, Robert’s wife) for solo piano, Brahms had been drawn to the form on many occasions, sometimes including a set of variations within a much larger work.

Yet independent, self-contained, sets of variations for orchestra were almost unheard-of at that time. Despite coming to compositional adulthood during the most significant era of Romantic music (broadly speaking, from the middle of the 19th-century), Brahms retained an abiding interest in composers of the 18th-century – in particular, JS Bach, Handel, Mozart and Haydn. When his attention was drawn by Carl Pohl – an early biographer of Haydn – in 1870 to a previously unknown Feld-Partita for wind band, attributed to Haydn, Brahms’ interest was aroused.

So much so in fact, that, three years later, Brahms took the theme (itself used as the subject for variations in the original Partita – when it was termed the St Antoni Chorale) as the basis for his own original set of variations. Perhaps the rarity of orchestral variations at that time led Brahms to compose the work both for two pianos and for symphony orchestra.

Interestingly, it was the two-piano version that was published first, by N. Simrock, in 1873, followed a year later by the orchestral version: more intriguingly, the orchestral version was termed Opus 56a, the two-piano version Opus 56b – so we cannot be certain which came first from Brahms’ pen. As if to complicate matters further, a version for piano duet (two pianists at one keyboard) by Robert Keller (Simrock’s Editor) appeared (with Brahms’ approval) in 1877. Indeed, so popular did this work become that Simrock issued transcriptions (neither by Brahms nor Keller) for various instrumental combinations, including one for solo piano, which Brahms admired and is known to have played himself on several occasions for friends.

However, it is the orchestral version which is heard most often today, and it is Brahms’ preferred version of this masterpiece that we hear in our concert of his music on this disc. It is interesting to note that Brahms acknowledged the original scoring for wind instruments by presenting the theme initially on the orchestra’s wind section, simply supported by pizzicato cellos and double- basses. The two-part St Anthoni chorale is then subjected to eight consecutive variations, each finely balanced within itself, flowing one after another, until the concluding variation, a passacaglia, heralds the arrival of a characteristic nineteenth-century coda.

The chorale theme is now known not to be an original by Haydn – although his name is appended today to the title in deference to Brahms, and is sanctioned by long usage, if not accurate in musicological terms. In the closing pages of this endearing masterpiece, the theme is now heard, sturdily triumphant, as the Variations stride to their uplifting conclusion.

Brahms had spent many years composing and revising his First Symphony (in C minor Opus 68) before he finally released it for performance in 1876, but his Second Symphony, in D major Opus 73, was written entirely during the summer and autumn of the following year. A large part of the new symphony was composed during an extended holiday in Pörtschach in the Carinthian Alps. The score was ready by October 1877 in time for the first performance on December 30 by the Vienna Philharmonic conducted by Hans Richter.

There is no doubt that the successful premiere of the C minor Symphony freed any doubts Brahms may have harboured over his symphonic abilities, and the success of that dramatic work prepared for the tremendous reception the Second Symphony enjoyed at its premiere a year later, the Viennese music- loving audience being clearly thrilled by the famous composer’s new-found symphonic mastery. The positive, outward-looking mood of the Second Symphony might well be more ‘approachable’ than that of the mighty C minor, but Brahms’ consummate skill and genuine symphonic sense of integration is no less subtle than in the previous work. Indeed, the Second Symphony reveals a depth of creative originality that contains Brahms’ genius just as admirably. It is surely equally true that the essentially relaxed nature of much of the work tends to hide, rather than obscure, Brahms’ profound mastery of his material.

The nature of the Second Symphony – its sunny, optimistic disposition, most of all – is enhanced by the wondrous sense of colour the music possesses, the opening three-note phrase on cellos and double-basses admirably setting the work’s sylvan scene, as well as being the melodic germ from which much of the succeeding themes and development are to grow. Brahms’ expressive qualities throughout the Symphony exude an atmosphere of flexibility and varied phrasing within the work’s carefully planned and executed proportions.

We can hear those qualities throughout the Symphony’s first movement, during which Brahms continues to build one of his broadest and most finely-expressive structures. In this music, we experience a subtly combined rhythm with lyrical aspects that flow equally throughout the Adagio second movement, which combines warmth and strength in a manner unmatched by any symphonic composer since Beethoven.

The third movement, Allegretto, brings a unique combination of fine delicacy and subtle humour, flavoured with what has been well described as twinkling vivacity. In the finale, Brahms’ release of the Symphony’s slowly growing inner tension is a further mark of the great composer: the music accepts occasional tragic overtones but it is inherently invigorating throughout. The means by which Brahms acknowledges the contemporaneous Romanticism of his fellow- composers, and reserving it for the moment that is psychologically the most suitable – the best, softest and tensest part before the restatement – demonstrates that here is pure music before the Symphony proceeds on its inherently outward-looking way to a wonderfully positive conclusion.

—Robert Matthew-Walker © 2022

Track Listing

- Allegro non troppo

- Theme: Chorale St. Antoni: Andante [02:17]

- Variation 1: Poco più animato [01:27]

- Variation 2: Più vivace [01:05]

- Variation 3: Con moto [02:02]

- Variation 4: Andante [01:52]

- Variation 5: Vivace [01:02]

- Variation 6: Vivace [01:32]

- Variation 7: Grazioso [02:58]

- Variation 8: Presto non troppo [01:09]

- Finale: Andante [03:55]

- I. Allegro non troppo [16:48]

- II. Adagio non troppo [09:57]

- III. Allegretto grazioso (quasi andantino) [05:46]

- IV. Allegro con spirito [10:34]

Tragic Overture, Op. 81 [14:56]

Variations on a Theme by Haydn, Op. 56a

Symphony No. 2, Op. 73