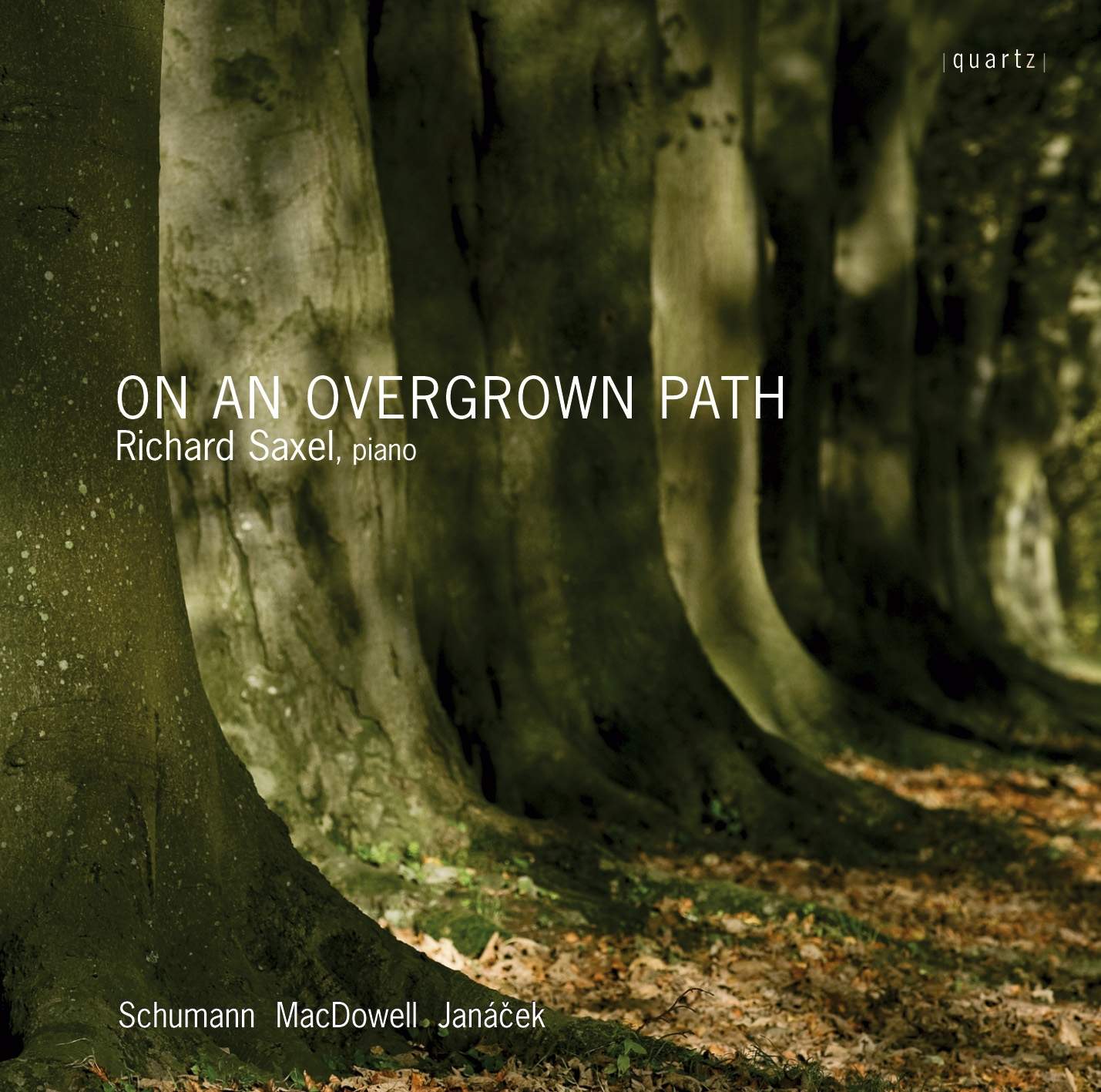

On an Overgrown Path

£4.99 – £11.99

Three of the best-loved works for piano focusing on woodland themes.

Robert Schumann (1810 – 1856)

Waldszenen, Op.82

Edward MacDowell (1860 – 1908)

Woodland Sketches, Op.51

;

Leos Janacek (1854 – 1928)

On an Overgrown Path – Book 1

About This Recording

In European and American literature, the forest has long been a powerful yet ambiguous symbol. Initially, however, such ambiguity did not exist, as in the classical world, the Dark Ages and the medieval period, it was associated primarily with danger and threat; from Virgil’s “antiquam silvam, stabula alta ferarum”, the shadowy, ancient wood that marked the entrance to the underworld, can be traced a line of descent through St. Augustine and the sinister Thor Forest of Irish mythology, culminating in Dante’s “selva obscura”, the dark forest in which Dante finds himself at the beginning of ‘Inferno’, which serves as a compelling, if tantalisingly imprecise, representation of the narrator’s spiritual and psychological bewilderment.

With the Renaissance, however, came a reinterpretation and reconsideration of the literary significance of the forest. For some, such as Edmund Spenser, its potential as a symbol of error and confusion was still irresistibly attractive and thus, in The Faerie Queene, we find the Redcrosse Knight, lost and bemused in a dark forest, beset by the embodiment of the beast Error. In Shakespeare, however, we see the roots being laid down of what would come to be the quintessentially Romantic conception of the forest as a potent topographical representation of freedom. In both A Midsummer Night’s Dream and As You Like It, the forest is a gloriously liberating place, in which the shackles of patriarchy, primogeniture and tyranny can be thrown off; a place in which a fairy queen might fall in love with a hapless weaver or in which the dictates of gender can be merrily ignored.

It was inevitably during the Romantic period that this conception of the forest reached its apotheosis, although it is worth noting that, in its early stages, some ambiguity still remains; for William Blake, the tiger, “burning bright, in the forests of the night”represents not only the wondrous beauty of God’s creation but also its awesome and dreadful power and the forest in these lines harbours both grandeur and threat. For the later Romantics, however, writing in an age of rapid industrial development, the forest came to represent everything that was most desirable about the human condition; a place where, as Keats puts it in Ode to a Nightingale, one will never know the ‘weariness, the fever, and the fret’ of urbanisation, a place where the nightingale’s song is a paean to the intransient splendours of the natural world, a world upon which the stench of effluence and the whirring of machines can never impinge. For Keats, the “forest dim” is far removed from Dante’s ‘selva obscura’ of doubt and horror, for it is in his description of the “white hawthorn and the pastoral eglantine”, the “verdurous glooms and winding mossy ways” that the extraordinary capacity of the forest to enchant and to delight is most memorably captured. Such an intuitive imaginative empathy with the blissful peace of the forest is equally evident in Shelley’s The Pine Forest of the Cascine near Pisa, in which the poet forges a stark contrast between the “inviolable quietness” of the forest and “Our mortal nature’s strife.” As with Keats, the forest is, for Shelley, a place of both quiet contemplation and an almost transcendental beauty, where “on the woods…the smile of heaven lay.”

The Romantic influence upon the artistic conception of the forest lasted for many years and can still be detected at the start of the twentieth century. Robert Frost certainly recognised the forest as a place of escape and retreat, most famously in Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening, in which the woods are described as “lovely, dark and deep”. They are used here as a powerful symbol of a yearning for freedom, born of individualism, as Frost uses a beautifully mellifluous sibilance – “the only other sound’s the sweep of easy wind and downy flake” – to present the woods as particularly seductive and alluring to a speaker who is all too aware of his own familiar

and professional responsibilities, ultimately acknowledging resignedly that he has “promises to keep”. There are few, if any certainties, in Frost’s verse, however, and, more than perhaps any other 20th century poet, it is Frost who recognises and then realises the ambiguous symbolic potential of the forest. In Birches, for instance, the enticing allure of ‘Stopping by Woods…’ has vanished, to be replaced by a “pathless wood”, used as a symbol for the onerous nature of adulthood, where “your face burns and tickles with the cobwebs Broken across it, and one eye is weeping From a twig’s having lashed across it open” There is evidently a dichotomy here in Frost’s presentation of the forest and is a dichotomy that has resonated throughout European and American literature for the best part of a thousand years. It can be both a place of safety and a place of threat: a place of liberation and a place of entrapment: a place of beauty and a place of darkness. It is this ambiguity which has ensured that, in the Western artistic tradition, the forest has continued to exercise such a powerful hold on our creative imagination.

© G.J.N. Neill, March 2010

ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810 – 1856)

‘Waldszenen’, Op. 82

Schumann wrote his Woodland Scenes in just nine days, beginning on 29th December 1848. The cycle of nine short pieces offers typically schizophrenic and ephemeral visions, in which the distinction between fantasy and reality is blurred. There are echoes of the childish simplicity of his Kinderszenen and the Album für die Jugend, and yet there are also moments of haunting other-worldliness that are far from the sensibilities of a child. The two outer movements Eintritt (Entrance) and Abschied (Farewell) are seemingly intrinsically linked; the gentle and yet excited opening becoming a nostalgic and poignant adieu, with each movement containing moments that are by turns real and unreal. In between come visions and descriptions of forest life, some straightforward, others less so. Two are energetic descriptions of hunters, as befits a work that took its original inspiration from Heinrich Laube’s Breviary of the Hunt (1841). Einsame Blumen (Solitary Flowers) is instilled with a beauty that is almost too fragile, whilst Freundliche Landschaft (Friendly Landscape) and Herberge (The Inn) offer a warm and welcoming respite. In contrast, Verrufene Stelle (A Haunted Place) and Vogel als Prophet (The Prophet Bird) inhabit an altogether different place. Verrufene Stelle is prefaced in the score with a poem by Friedrich Hebbel:

‘The flowers, so rankly growing,

Are pale and like the dead.

Yet one there is amongst them

That glows a dusky red.

It did not gain its colour

From sunlight’s warming flood;

It took it from the cold earth

That’s soaked in dead men’s blood.’

(trs. Howard Ferguson)

The mood is unsettling in the extreme, and Clara Schumann is said to have omitted it whenever she performed the work. Vogel als Prophet contrasts delicate arabesques with a hymn-like central section perhaps reminiscent of The Poet Speaks from Kinderszenen.

EDWARD MACDOWELL (1860 – 1908)

‘Woodland Sketches’, Op. 51

Edward MacDowell was a highly educated musician: composer, pianist, teacher and lecturer, he achieved widespread recognition in his native America during his lifetime. His style was heavily influenced by German Romanticism, perhaps inevitably given his early training at the Paris Conservatoire and in Frankfurt under Joachim Raff. By the time the Woodland Sketches were published in 1896, MacDowell had returned to America, settling in Boston, and was enjoying the most successful period of his career. The Woodland Sketches are instilled with simple charm, allowing them to stand as both enduringly popular miniatures and as a suite which assumes a rather nostalgic disposition. Each little piece contains an honesty of purpose and a clearly defined character, and whilst some of them are technically not difficult, others, Will o’ the Wisp, In Autumn, By a Meadow Brook, betray the hallmark of MacDowell’s virtuoso pianism, if only briefly. To a Wild Rose is perhaps the most memorable tune MacDowell ever wrote. Its simple tenderness is beautiful; a quality echoed in several of these miniatures (At an Old Trysting Place, To a Water Lily, A Deserted Farm). Each manages to avoid sentimentality by virtue of inherent honesty, and this is effectively contrasted with the humour of From Uncle Remus and the rather stern quality of the Brotherton Indian melody used in From an Indian Lodge. The cycle is drawn together both dramatically and thematically by the concluding Told at Sunset. The parallels with Schumann’s similarly titled work are understated, and the differences marked; it is certain that MacDowell would have known Schumann’s work well, and would have recognised the touch of genius that illuminates Waldszenen. Compare, for example, To a Wild Rose and Einsame Blumen (Solitary Flowers): a subtle deference perhaps?

LEOS JANÁČEK (1854 – 1928)

‘On an Overgrown Path’

The genesis of On an Overgrown Path is long and complicated, and begins with a request in 1897 from a Moravian teacher that Janacek might contribute to a collection of harmonium pieces he was publishing. The final collection of ten pieces was published separately in December 1911, some three years after its completion. Janáček writes in a letter dated 6th June 1908 that ‘…The little pieces On an Overgrown Path contain distant reminiscences. Those reminiscences are so dear to me that I do not think they will ever vanish.’

On an Overgrown Path is a recollection and re-exploration of sorrow; Janáček had lost his beloved daughter Olga in 1901, and the cycle contains ‘suffering beyond words’. It also contains genuine warmth, and a gravitas that comes from a composer seeking not to write beautiful music, nor to be clever, but to express the depth and profundity of intense human emotion. Slavic folk music was a major source of musical inspiration to Janáček throughout his life, and the style infuses this collection of little pieces. His music is not necessarily conceived with the piano in mind; some pieces in the cycle were originally written for the harmonium, and others contain motives more suited to the cembalo or zither. Janáček was also fascinated with the sounds and rhythms of human speech and the natural world, and so to understand his intentions it is necessary also to consider these sound worlds and not just to rely on accepted pianistic techniques. He asks that every note be played ‘as if dipped in blood’, and that the music consist ‘not just of roses, but also of thorns’.

The first five pieces are memories of his Moravian youth: family evenings, a blown away leaf, childish games, the dark church on the hill at Hukvaldy (as a boy Janáček had sung in the choir at the monastery in Brno), and village gossips chattering away. The latter pieces explore the anguish and desolation caused by premature death, a moment of weeping and then the haunting screeching of the barn owl, the harbinger of death in Moravian folklore. ‘The barn owl is still there, screeching: it prophesies death.’

© Richard Saxel, October 2009

Track Listing

-

Robert Schumann

- Waldszenen (i) Entry

- Waldszenen (ii) Hunter on the Watch

- Wadszenen (iii) Solitary Flowers

- Waldszenen (iv) Sinister Place

- Waldszenen (v) Friendly Landscape

- Waldszenen (vi) The Inn

- Waldszenen (vii) The Prophet Bird

- Waldszenen (viii) Hunting Song

- Waldszenen (ix) Farewell Edward MacDowell

- Woodland Sketches (i) To a Wild Rose

- Woodland Sketches (ii) Will o' the Wisp

- Woodland Sketches (iii) At an Old Trysting Place Robert Schumann

- Woodland Sketches (iv) In Autumn

- Woodland Sketches (v) From an Indian Lodge

- Woodland Sketches (vi) To a Water Lily Edward MacDowell

- Woodland Sketches (vii) From Uncle Remus

- Woodland Sketches (viii) A Deserted Farm

- Woodland Sketches (ix) By a Meadow Brook

- Woodland Sketches (x) Told at Sunset Leos Janacek

- On an Overgrown Path (i) Our Evenings

- On an Overgrown Path (ii) A blown-away leaf

- On an Overgrown Path (iii) Come with us!

- On an Overgrown Path (iv) The Frydek Madonna

- On an Overgrown Path (v) They chattered like swallows

- On an Overgrown Path (vi) Words Fail!

- On an Overgrown Path (vii) Good Night!

- On an Overgrown Path (viii) Unutterable anguish

- On an Overgrown Path (ix) In tears

- On an Overgrown Path (x) The barn owl has not flown away!