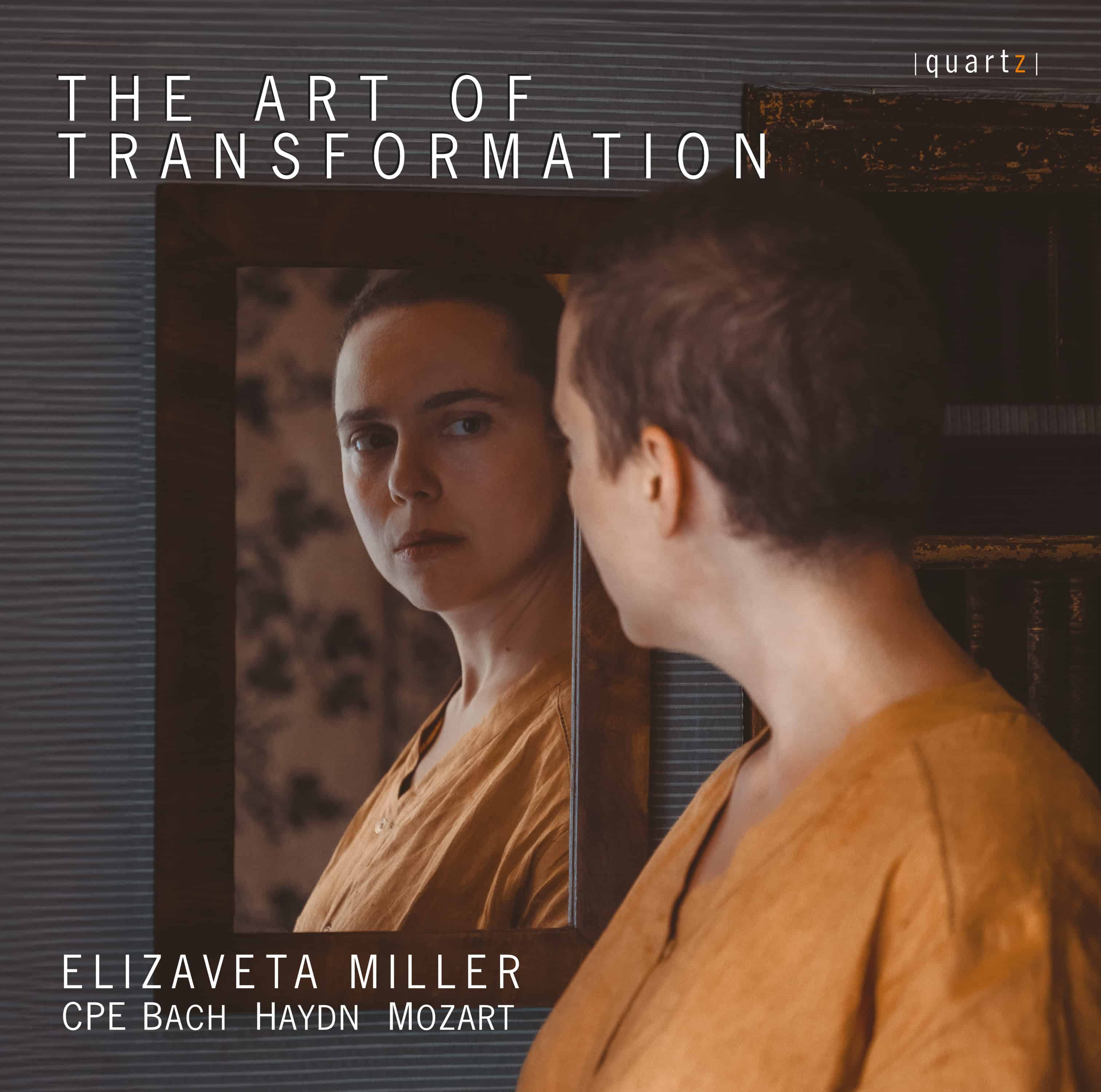

The Art of Transformation

Price range: £7.99 through £16.99

Music of the classical and pre-classical periods is the language of ideas and gestures. Musical gesture becomes intelligible by recurrence and recognition. Turning an idea on one’s tongue, trying it out in slightly different wording, with a new intonation and in a changed voice creates the musical discourse — the story told, or the argument held. This is the definition of variation, and variation lies at the heart of musical expression.

The sonata form is sometimes considered nowadays as the greatest achievement of musical thought of that period, but composers of the 18th century were happy to turn to more humble forms. Of these, Variations and Fantasias are probably those with the most distinguished histories. In Variations, an idea is confined to the simplest frame of a musical period, unable to break its own formal boundaries, but free to mutate in all possible ways inside them; in the Fantasia, a musical thought is born, develops and flourishes with no seeming restraint, but for the free will of the composer to structure this flow, and yet, they have in common this constant tension between the urge to repeat an idea and the necessity of altering, transforming it. This hidden conflict feeds creativity and the imagination: it generates, ultimately, the classical style.

About This Recording

The Art of Transformation

Music of the classical and pre-classical periods is the language of ideas and gestures. Musical gesture becomes intelligible by recurrence and recognition. Turning an idea on one’s tongue, trying it out in slightly different wording, with a new intonation and in a changed voice creates the musical discourse – the story told, or the argument held. This is the definition of variation, and variation lies at the heart of musical expression.

The sonata form is sometimes considered nowadays as the greatest achievement of musical thought of that period, but composers of the 18th century were happy to turn to more humble forms. Of these, Variations and Fantasias are probably those with the most distinguished histories. In Variations, an idea is confined to the simplest frame of a musical period, unable to break its own formal boundaries, but free to mutate in all possible ways inside them; in the Fantasia, a musical thought is born, develops and flourishes with no seeming restraint, but for the free will of the composer to structure this flow. And yet, they have in common this constant tension between the urge to repeat an idea and the necessity of altering, transforming it. This hidden conflict feeds creativity and the imagination: it generates, ultimately, the classical style.

CPE Bach’s Fantasia in C Major closes to the fifth collection of sonatas and fantasias Für Kenner und Liebhaber. Many features relate it to the sonata form. Two contrasting themes, an ascending arpeggio with a playful “cuckoo” answer, Andantino, and an intimately speaking Allegretto with elements of

sighing Lamento, are presented, varied and then return in what clearly makes us think of an exposition-development-recapitulation scheme. However it is the connecting material that plays a crucial role in the originality of this piece. Tempi change constantly, ranging from prestissimo furious passages to suspended sequences of diminished chords, each arpeggiated measure ending with a fermata, and offer to the listener a kaleidoscope of affects and mood-twists. CPE Bach is extremely controlling of the nuances, phrasing and articulation in this fantasia, as in many of his late works, but there is enough space left for the performer to experiment with timbre, shades and especially time.

The 12 Variations on the Folie d’Espagne are not typical for CPE Bach. Most of his variation cycles were written earlier. The Folia, an eternal hit of the variation genre, had already received several iconic settings by the time CPE Bach turned to them in 1778. His approach, however, is far from traditional. If there was a possible comparison, it could be with Anton Webern’s variations for piano Op. 27. All structural aspects are subject to change, except for the number of measures in the period. The texture gets unpredictable treatment, with almost pointillistic gestures alongside simple two voice polyphonic settings, and furious passagework giving way to chordal textures, adorned with manically precise dynamic markings.

Haydn’s Fantasia in C gives one of the most famous examples of humor in instrumental music. The joyful energetic beginning opens a whole hunting scene, with hounds and prey racing, horns sounding far away, drawing nearer, exploring all the range and possibilities of the fortepiano, while constructing, in Haydn’s signature way, the whole piece with only several simple motifs.

In maximal contrast with the Fantasia, Haydn’s Andante with Variations in F minor is one of the most complex and serious of his piano pieces. It has a grandeur that no other variation cycle by Haydn shares, and the marking Sonata in the manuscript hints at a larger scale project, of which this could be the first movement. Both the minor and major periods that form the double theme receive a refined and inventive treatment, and demand great precision and virtuosity from the performer. The final (da Capo) variation leads into a large improvisational section that reminds the listener of CPE Bach’s free fantasias.

Mozart’s Variations in B flat, K. 500, are not the most popular in his output, and one of the reasons is probably its extreme virtuosity combined with a more than simple, almost primitive theme of two 4-bar sentences. The cycle displays the canonic structure of classical variations, with a texture that gradually speeds up, an Adagio penultimate variation that calls to the performer for embellishments and an extended vivace finale. The simple nonchalance of the theme gives the whole piece a graceful and

lightheartedness and easily generates Mozart’s signature tender witticism.

Finally, the album closes with Mozart’s Fantasia in C minor K. 475, his enigmatic masterpiece. Its popularity among pianists has anchored an iron- cast version in our ears that is very difficult to ignore and to alter. The overall structure, the making of it, however, is revealed to someone who is familiar with CPE Bach’s chapter on free fantasia in his Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments. That the episodes of Mozart’s Fantasia are, in fact, built on a harmonization of part of an ascending scale with a modulating sequence (c-D-E (dominant to a)-F-Bb-g-c) is not an obvious, and yet an enlightening thought.

It allows to transcend a romanticised perception of the piece and to connect it to a bigger scale musical scenery of its time.

To construct a programme based on two minor and seemingly contrasting genres of Variations and Fantasia represented for me a quest into that which I feel to be the heart of the classical style – the coexistence of extreme freedom and extreme restraint, in form, in notation, in expression. This combination is at once contradictory and inspiring: it embodies the tensions at the heart of life.

L’Art de la Transformation

Le langage de la musique classique et préclassique est celui des idées et des gestes. Le geste musical devient intelligible par sa récurrence et la reconnaissance de l’auditeur. Tourner une idée sur sa langue, la reformuler légèrement, tenter une nouvelle intonation aide à former le discours. C’est la définition de la variation, et la variation est au cœur de l’expression musicale.

La forme sonate est parfois considérée comme le sommet de la pensée musicale de cette période, mais les compositeurs du XVIIIe siècle s’adressaient aussi volontiers à des formes plus modestes. Parmi celles-ci, les Variations et les Fantaisies ont probablement les origines les plus distinguées. Dans les Variations, une idée est confinée au cadre très simple d’une période musicale, y est limitée formellement, mais garde la liberté de se transformer à l’intérieur; dans la Fantaisie, une pensée musicale naît, se développe et s’épanouit sans contrainte apparente, si ce n’est la volonté du compositeur. Et pourtant, elles ont en commun cette tension constante entre le désir de réitérer une idée et la nécessité de la transformer. Ce conflit alimente la créativité et l’imagination: il engendre, en fin de compte, le style classique.

La Fantaisie en do majeur de CPE Bach est la dernière pièce du 5e recueil de sonates et fantaisies Für Kenner und Liebhaber. De nombreuses caractéristiques la rattachent à la forme sonate. Deux thèmes contrastants, un arpège ascendant avec une réponse ludique de type “coucou”, andantino, et un allegretto au caractère intime avec des éléments de lamentation, sont présentés, variés, puis reviennent dans ce qui évoque clairement un schéma

d’exposition-développement-récapitulation. Mais ce sont les épisodes et les ponts qui jouent un rôle crucial dans l’originalité de cette pièce. Des furieux prestissimo Bach passe à des séquences suspendues d’accords diminués, chaque mesure arpégée se terminant par une fermata, offrant à l’auditeur un kaléidoscope d’affects et de retournements d’humeur. CPE Bach exerce un contrôle extrême des nuances, du phrasé et de l’articulation dans cette fantaisie, comme dans bon nombre de ses œuvres tardives, mais il laisse suffisamment d’espace au musicien pour jouer sur le timbre, les nuances et surtout le temps.

Les 12 Variations sur la Folie d’Espagne ne sont pas typiques de CPE Bach. La plupart de ses cycles de variations ont été écrits bien plus tôt. La Folia, un succès éternel du genre variation, avait déjà reçu plusieurs interprétations emblématiques à l’époque où CPE Bach s’y est attaqué en 1778. Cependant, son approche est loin d’être traditionnelle. Si une comparaison était possible, ce pourrait être avec les variations pour piano op. 27 d’Anton Webern. Tous les aspects structurels sont sujets à des changements, à l’exception du nombre de mesures dans chacune des variations. La texture est traitée de manière imprévisible, avec des gestes presque pointillistes aux côtés de configurations polyphoniques simples à deux voix, et des passages furieux laissant place à des textures harmoniques, ornées de marques dynamiques de grande précision.

La Fantaisie en do majeur de Haydn offre un des exemples les plus célèbres d’humour en musique instrumentale. Le début joyeusement énergique s’ouvre en une scène de chasse, avec des chiens et le gibier qui court, des cors qui sonnent au loin, se rapprochant, explorant toute la gamme et toutes les possibilités du pianoforte, tout en construisant, à la manière caractéristique de Haydn, toute la pièce à partir de plusieurs motifs très simples.

En contraste maximal avec la Fantaisie, l’Andante avec Variations en fa mineur de Haydn est une de ses pièces pour piano les plus complexes et sérieuses. Elle possède une grandeur que ne partage aucun autre cycle de variations de Haydn, et l’indication “Sonata” dans le manuscrit laisse présager un projet de plus grande envergure, dont elle pourrait être le premier mouvement. Les périodes mineur et majeur qui forment le double thème reçoivent un traitement raffiné et inventif, exigeant une grande précision et virtuosité de la part de l’interprète. La variation finale (da Capo) mène à une grande section improvisée qui rappelle au public les fantaisies libres de CPE Bach.

Les Variations en si bémol majeur de Mozart, K. 500, ne sont pas les plus populaires de son œuvre. Une des raisons en est probablement leur virtuosité extrême, alors que le thème est presque primitif, constitué de deux phrases de quatre mesures. Le cycle présente la structure canonique des variations classiques, avec une texture qui s’accélère progressivement, une variation pénultième en adagio qui invite l’interprète à l’ajout

d’ornements, et une finale vivace étendue. La nonchalance simple du thème confère à l’ensemble une grâce et une légèreté et génère facilement le trait d’esprit tendre caractéristique de Mozart.

Enfin, l’album se termine avec la Fantaisie en do mineur de Mozart, K. 475, son énigmatique chef-d’œuvre. Sa popularité auprès des pianistes a ancré une version inaltérable dans nos oreilles qu’il est très difficile d’ignorer et de modifier. La structure globale, sa création, cependant, est révélée à celui qui est connaît bien le chapitre de CPE Bach sur la fantaisie libre dans son Essai sur l’Art de Jouer des Instruments à Clavier. Que les épisodes de la Fantaisie de Mozart reposent en réalité sur une harmonisation d’une progression qui combine une partie de gamme ascendante et une séquence modulante (do- ré-mi (dominante vers la-la)-fa- si bémol- sol-do) voilà qui n’est pas une pensée évidente, et pourtant, c’est une pensée éclairante. Elle permet de dépasser une perception romantique de la pièce et de la replacer sur la scène musicale plus vaste de son époque.

En me dans l’enregistrement du programme basé sur ces deux genres en apparence contrastés,,ce qui représente pour moi une quête au cœur du style classique, j’ai voulu explorer la coexistence de la liberté extrême et de la contrainte extrême, dans la forme, dans la notation, dans l’expression. Cette combinaison est à la fois contradictoire et inspirante : elle incarne les tensions au cœur de la vie.

Produced by Slava Poprugin, Steppenwolf Studio

The recording was made on the 20–24 December 2018

at the Chris Maene Workshop in Ruislede on the copy of a fortepiano by Anton Walter, Vienna, 1795 by Chris Maene and with his generous help and assistance

Photos by Ana Vledouts

Track Listing

- Fantasia in C Major, H. 284

- 12 Variations Upon the Folie D’Espagne, H. 263

- Fantasia in C Major, Hob. XVII:4

- Variations in F Minor, Hob. XVII:6

- Twelve Variations in B Flat on an Allegretto K. 500

- Fantasia in C Minor, K. 475