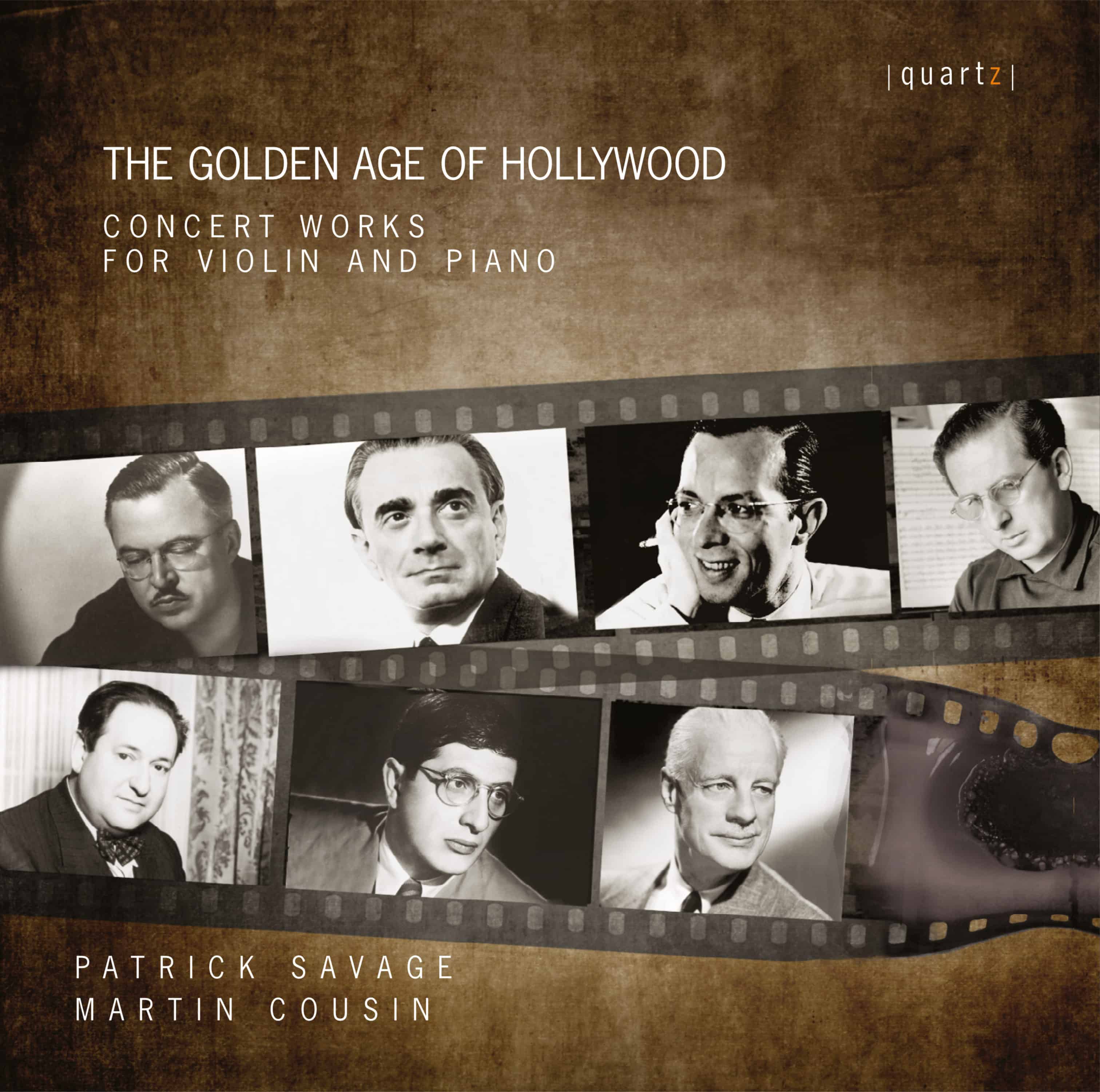

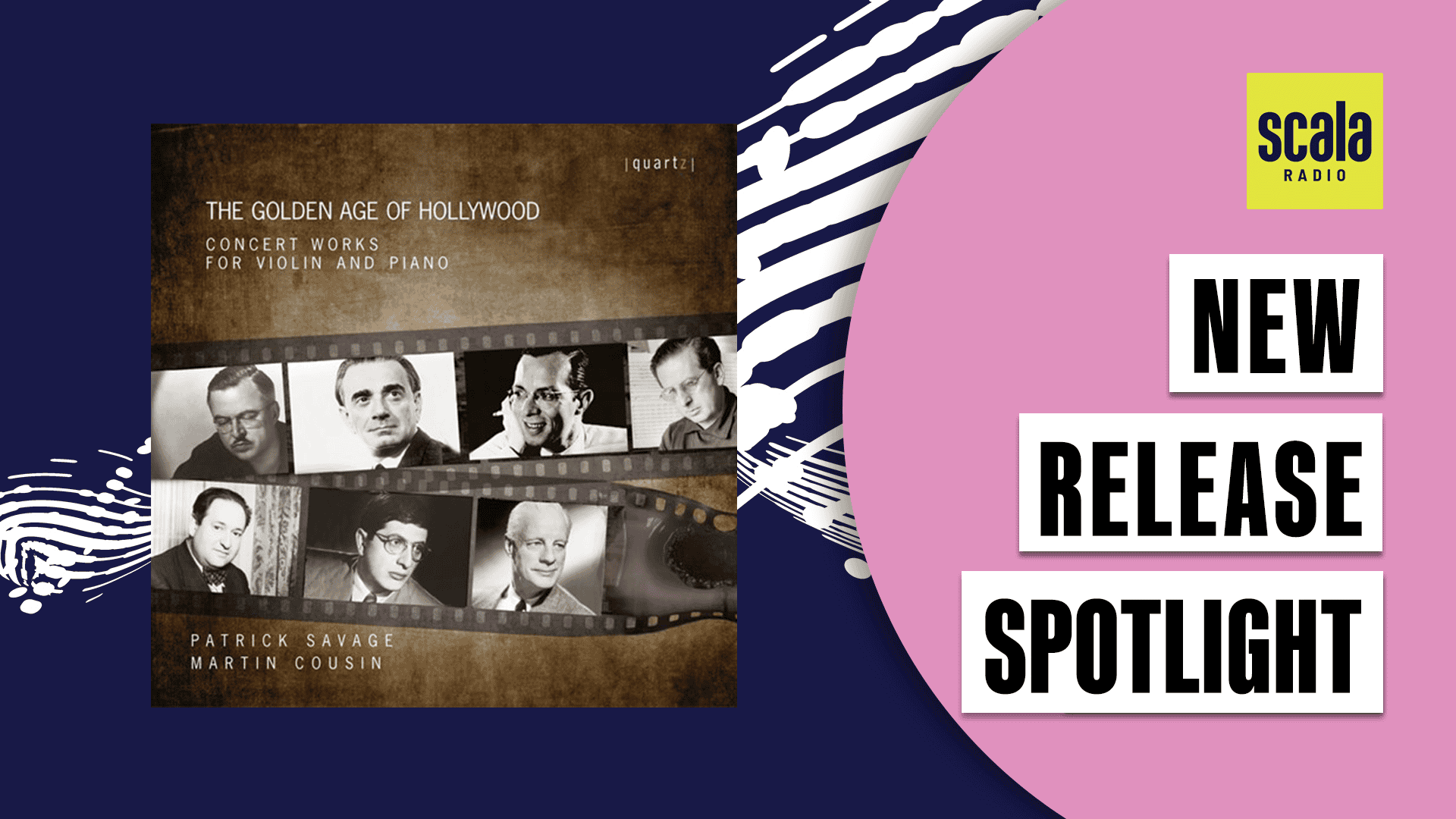

The Golden Age of Hollywood: Concert Works for Violin and Piano

£7.99 – £16.99

A remarkable album of concert works by legendary composers of Hollywood’s Golden Age will be released on the Quartz label on 5 April, 2024. The recording features music for violin and piano by Erich Korngold, Franz Waxman, Bernard Herrmann, Miklós Rózsa, Robert Russell Bennett, Jerome Moross and Heinz Roemheld. Much of the music is rarely heard and the album features three world premiere recordings.

Australian-born violinist Patrick Savage researched and compiled the program during COVID lockdowns and performs the works alongside pianist Martin Cousin.

Formerly Principal First Violin for the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and first violin in the Tippett Quartet, Patrick is now a free-lance concertmaster, soloist, studio session player and West End musician. He is also a composer for feature film, theatre and video games, and his film scores include the cult horror THE HUMAN CENTIPEDE and the forthcoming puppet horror, ABRUPTIO.

Each of the composers represented on this album were Academy Award-winners or nominees and made an extraordinary contribution to the art of film scoring during Hollywood’s Golden Age – the heady years of frenetic film production from the 1920s to the 1960s. Between them they composed scores for some of the most famous cinema of the era.

Extraordinary music-makers were drawn to Los Angeles from across the United States and around the world, including those forced to flee the rise of Nazism in Europe. But even the most gifted of composers that made their name in cinema often faced an uphill battle for acceptance in the classical world. Professional jealousy may have been a factor, as well as snobbery: how could a composer for popular entertainment be taken seriously as an artist?

This prejudice led to music of great value remaining in obscurity, but despite a resurgence of interest in film composers of those years, the works by Herrmann, Roemheld and Moross are recorded here for the first time.

“For each of the exceptional composers represented on this recording, a gift for film scoring was just one aspect of their creative powers. Though these artists were united by a dedication to lyricism and a rejection of atonality, their backgrounds and influences were markedly diverse. We have aspired to present a program that represents the extraordinary richness, colour and imagination of their musical offerings for the concert hall, and it is a great honour to be granted the opportunity to record several of these works for the very first time”. —Patrick Savage

Track Listing

- Maiden In The Bridal Chamber 3’10

- March of the Watch (Dogberry and Verges) 2’20

- Garden Scene 4’40

- Masquerade (Hornpipe) 2’34

- Good Morning 2’06

- Promenade 1’56

- Playtime 0’41

- Bedtime Story: The Fairy Princess 3’57

- Gut-Bucket Gus 2’13

- Jane Shakes Her Hair 1’14

- Betty And Harold Close Their Eyes 1’43

- Jim Jives 0’59

- _ _ _ Till Dawn Sunday 2’07

- Fast and Deliberate 3’38

- Sempre senza vibrato 3’52

- Very fast 3’07

- Recitative and Aria for Violin and Piano Jerome Moross 6’03

- Pastoral (Twilight) Bernard Herrmann 6’55

- Variations on a Hungarian Peasant Song Miklós Rózsa 9’15

Press Reviews

THE GOLDEN AGE OF HOLLYWOOD CONCERT WORKS FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO

Each of the composers represented on this album made an extraordinary contribution to the art of film scoring during Hollywood’s Golden Age – the era from the 1920s to the 1960s of frenetic film production, transformational technical innovation and movie-star glamour, when the giant film studios were at their zenith. Music-makers were drawn to Los Angeles from across the United States and around the world, including many fleeing post-First World War Europe and the rise of Nazism.

Our featured composers were Academy Award-winners or nominees, each producing a formidable body of work for cinema. This album, however, does not include music derived from film scores but is a celebration of their musical lives beyond film. This is repertoire for the concert hall, written while the composers worked in Hollywood or in the years preceding.

During those times, composers that made their name in Hollywood faced an uphill battle for acceptance in the classical music world. Professional jealousy was a factor, as was snobbery: could a composer for mass entertainment really be taken seriously as an artist?

In recent years there has been a resurgence of interest in the film composers of those years, but much music of great value remains in relative obscurity. In this album we include works by Hollywood icons Bernard Herrmann, Heinz Roemheld and Jerome Moross, recorded for the very first time.

ERICH KORNGOLD (1897–1957) Much Ado About Nothing 1920

At an early age, Korngold was the toast of Europe. In his earliest compositions, his lyrical, richly chromatic musical identity was miraculously fully formed and he was feted as the greatest prodigy of his day.

Director, Max Reinhardt, invited Korngold to compose for his Vienna production of Much Ado About Nothing, and an orchestral suite drawn from the incidental music was premiered by the Vienna Philharmonic in 1920 followed soon by the four- movement arrangement for violin and piano.

American audiences were introduced to Korngold via the cinema after Reinhardt invited him to Hollywood to score A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1934 for Warner Bros. The rise of Nazism made his return to Austria impossible.

Though his extraordinary film scores transformed the music of Hollywood, by the end of the Second World War Korngold had become disillusioned with the industry and returned to composing for the concert hall. However, tastes had changed and the late romantic lyricism of Korngold, so perfectly suited to Hollywood, had become the music of the past.

FRANZ WAXMAN (1906–1967) Four Scenes of Childhood 1948

Waxman’s name was made in Germany as the pianist for Weintraub’s Syncopators, a jazz band renowned as a high-class cabaret fixture. As the band’s arranger and songwriter, this led to high-profile work in German cinema. In 1933, the increasingly threatening political climate forced him to depart for France and then the United States.

Almost in spite of his rise to fame as a prolific film composer in Hollywood, Waxman established a parallel career as a classical conductor. Founding the Los

Angeles Music Festival in 1947, he sought to mine the wealth of émigré musical talent to raise the profile of classical music in the city – especially new music.

His rarely heard Four Scenes of Childhood suite was a gift to his friend, the great violinist, Jascha Heifetz, in 1948 on the birth of Heifetz’ son, Jay. Sadly, there’s no Heifetz recording of this effortlessly charming, joyful work, and the music was only rediscovered in Heifetz’ sheet music library after his death.

Each movement is a loving sketch of idealised family life, beginning with the early morning chimes of the clock in the piano and the long violin line descending from dreamland into the dawn light. After two movements of playtime frolicking and a bedtime fairy tale in the final movement, the opening violin line is mirrored in reverse, followed by the night chimes of the piano as we drift off to sleep.

ROBERT RUSSELL BENNETT (1894–1981) Hexapoda: Five Studies in Jitteroptera 1940

Inspired by swing-dancing, the title playfully references the imaginary, six-legged jitterbug insect. Composed at great speed on the prompting of the legendary studio violinist, Louis Kaufman, the suite was premiered by Jascha Heifetz to great popular reception and critical acclaim.

Reviewing the premiere, the New York Herald Tribune, wrote of the movements:

“…they are evocative of swing music without themselves being swing music…They are, in addition, magnificently written for the violin.”

From a highly musical family in Kansas City, Missouri, Robert Russell Bennett is best known for his extraordinary impact as an orchestrator on Broadway and in his film adaptations of iconic musicals. In 1956, Bennett won an Academy Award for his score of Rogers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma, and his music for Pacific Liner gained him an original score Oscar nomination in 1939.

Bennett wrote prolifically for the concert hall, though struggled to reconcile the two sides of his musical life, having been taught by his mother at an early age that popular music was “trash”.

HEINZ ROEMHELD (1901–1985) Sonatina 1950

Born to German parents in Milwaukee, Roemheld’s long career transcended musical genres and comprised a colossal volume of film titles and concert works. A child prodigy on the piano, he studied in Berlin before returning the United States where he worked in silent film theatres conducting and playing the piano.

The charming, exuberant first movement of the Sonatina, with a nod towards Poulenc and Milhaud, draws on dance rhythms, jazz-influenced harmony and more traditional conventions such as the extended fugato passage that leads to the climax of the movement.

The slow movement, marked Sempre Senza Vibrato, sees a simple, hypnotic melody looping in the violin, played in plain, almost childlike fashion, as the piano in contrast becomes ever more intricate.

The finale is a jocular moto perpetuo, giving way to a coda that reflects on the second movement in piano before a dramatic return to the first movement theme for solo violin.

JEROME MOROSS (1913–1983) Recitative and Aria 1941

Despite the extraordinary influence of Moross’ movie music, he regarded film writing as enabling the pursuit of his true calling: composing for the theatre and the concert hall.

Moross’ early focus turned from serialism towards establishing an authentic American sound, drawing on popular idioms from across the United States. In that pursuit he was allied with Aaron Copland, who invited him to orchestrate the film score, Our Town.

With the earthy physicality of his music, it seems inevitable now that Moross should score Westerns, and his Oscar-nominated score for The Big Country in 1958 was a landmark in the genre, heavily influencing Western scores that followed.

We hear the rugged spirit of the Western throughout the Recitative and Aria for violin and piano. Opening with the lonely, declamatory voice of the violin in the improvisatory Recitative, the music builds in intensity and rhythmic energy to a furious peak, subsides, and then launches the piano into the sturdy, muscular cantering rhythm of the Aria, marked “Moderato – Unhurried”. The coda ushers back the lonely voice of the opening, before fading into silence.

BERNARD HERRMANN (1911–1975) Pastorale (Twilight) 1929

One of the most celebrated, influential film composers of the 20th century, Bernard Herrmann’s name is often associated with his long-standing collaborator, director Alfred Hitchcock. Herrmann was born in New York to Russian Jewish parents and showed early promise as a composer and conductor.

In his film scoring work he was fiercely independent, believing in creative freedom unencumbered by directorial intervention, and he was endlessly innovative with his

use of pioneering recording techniques, electronics and non-traditional orchestration.

The Pastorale (Twilight) manuscript exists in both viola and violin versions and was composed ten years before he scored his first film.

With clear influences from Debussy and Ravel, Herrmann is exploring his musical identity in this work, but distinctive harmonic elements that pervaded his scores are already recognisable. In the gentle, meditative violin line we hear an unusually lyrical Herrmann, and his experimental spirit is evident with the peculiarly unequal partnership between the two instruments, with the piano occasionally set free to explore solo, quasi-improvisatorial episodes.

MIKLÓS RÓZSA (1907–1995)

Variations on a Hungarian Peasant Song, Op.4 1929

Steeped in the tradition of Hungarian folk music and heavily influenced by Bartok, Rozsa introduced a fresh musical language to Hollywood at a time that filmmakers were averse to dissonance. Rozsa composed for almost a hundred films, notably the great historical epics such as Ben-Hur, El Cid and Quo Vadis.

From early in his career, Rozsa divided his professional identity in two, writing light music in Paris under the nom de plume, “Nic Tomay” to protect his name. Even as a long-established film composer in Hollywood, Rozsa considered his film work to be primarily a means for paying the bills, and his 1952 contract at MGM granted him three months of every year to decamp to Italy to focus on his concert music, which Rozsa described as his “serious” work.

Variations on a Hungarian Peasant Song is drawn from the folk music that he was to return to repeatedly in his concert music, and his background as a violinist is apparent in the ease, variety and imagination of the virtuosic writing.