Ysaÿe: Sonatas & Étude Posthume

£7.99 – £14.99

Ysaÿe’s solo violin sonatas display Bach’s influence, alongside 20th-century stylistic traits including quarter tones, whole tone scales, and astringent dissonances. The works also include the spirit of their young dedicatees, all of whom were violinists and some composers as well.

Ysaÿe sought in these sonatas to convey the evolution of violin music, covering a broad historical and geographical range. Indeed the dedicatees represent an array of different nationalities; as Ysaÿe once stated “…real art should be international”.

Boris Brovtsyn has established himself as one of the most profound and versatile musicians of his generation, he is in increasing demand throughout the world both as a soloists and concerto performer. He has recorded for many labels including Naxos.

This recording sees the rarely recorded Étude posthume.

About This Recording

Eugène Ysaÿe was born into a family of violinists in Liège in 1858. He showed a prodigious aptitude for the instrument, and entered the Liège Conservatoire aged only seven. At 16 he travelled to Brussels, where he studied with Henri Vieuxtemps and Henryk Wieniawski whom, according to Hungarian violinist Joseph Szigeti, Ysaÿe considered “the greatest of his contemporaries”. In Paris he met the Russian pianist- composer Anton Rubinstein, who had a lasting impact on his musical sensibilities, after which Ysaÿe travelled to Berlin, where he became a founding member of the Berlin Philharmonic.

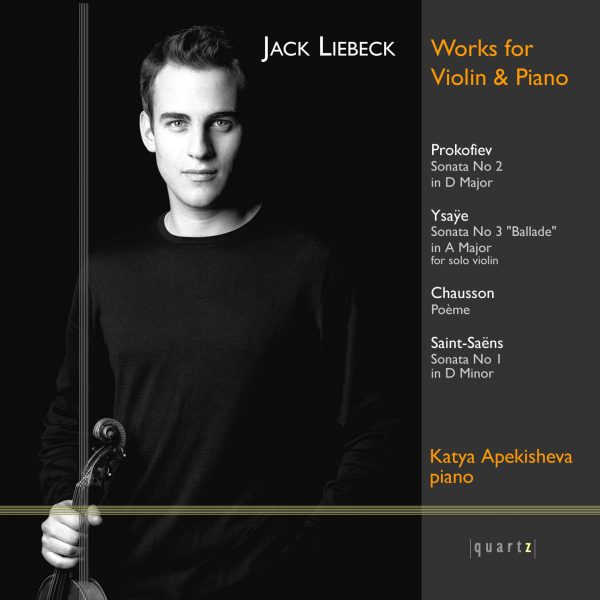

On his return to Paris in 1883, Ysaÿe became part of the “bande à Franck” surrounding his fellow Belgian composer, César Franck. Ysaÿe’s formidable skills were swiftly recognised, and many works were composed for, or dedicated to, the violinist, including Franck’s Violin Sonata, Chausson’s Poème, and the string quartets of Saint-Saëns, Debussy, and Vincent d’Indy.

At the peak of his powers, Ysaÿe was regarded as the foremost violinist of his generation. Diabetes caused his health to deteriorate, however, and Ysaÿe began to devote more time to composition. The Six Sonates pour violon seul were composed in July 1923, inspired by a performance of J.S. Bach’s Sonata for solo violin in G minor (BWV 1001) given by Joseph Szigeti (1892-1973). Ysaÿe produced sketches for all six works in just 24 hours.

Ysaÿe’s Solo Violin Sonatas display Bach’s influence, alongside 20th century stylistic traits including quarter tones, whole-tone scales and dissonance. They also communicate something of the spirit of each of their young dedicatees, who represent an array of different nationalities; as Ysaÿe once stated: “… real art should be international.”

The Sonata No.1, dedicated to Szigeti, reveals the influence of Bach in its structure and style, the opening movement marked Grave and the second a neoclassical Fugato. Yet the folk music of Szigeti’s native Hungary, with its distinctive modal inflections, also infiltrates the sonata, creating an intriguing fusion of elements.

Subtitled ‘Obsession’, the Sonata No.2 is dedicated to the French violinist Jacques Thibaud (1880-1953), who toured with Romanian violinist-composer George Enescu, dedicatee of the Sonata No.3, and who taught the Sixth Sonata’s dedicatee, Spanish violinist Manuel Quiroga. Thibaud invariably played the Prelude to Bach’s Partita No.3 in E (BWV 1006) as a warm-up exercise, and Ysaÿe duly quotes the work throughout this sonata, alongside references to the Dies irae (“day of wrath”) plainchant from the Latin Requiem Mass. In juxtaposing these elements Ysaÿe creates a sort of musical collage, reflecting wider trends in early 20th century art such as the paintings of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque.

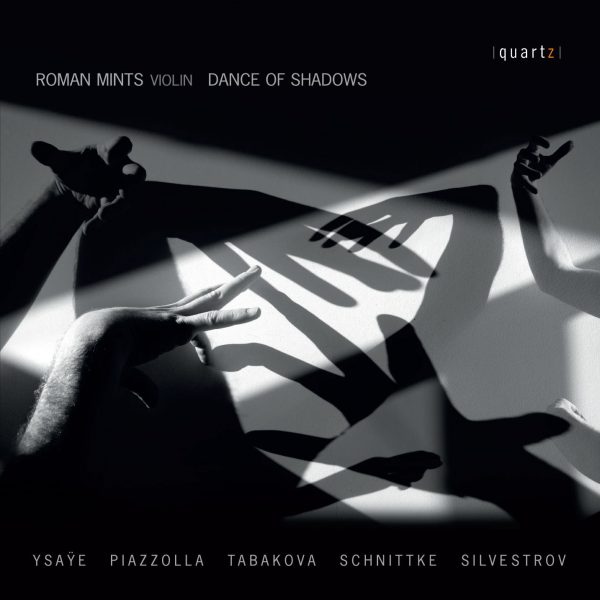

Ysaÿe’s movement titles in the Sonata No.2 are more impressionistic than those of the First Sonata: there is the Obsession of the first movement, with its tenacious tussle between Bach and the plainchant, followed by Melancholy, then a Dance of Shadows and, finally, The Furies, in which scordatura tunings create acerbic dissonances.

Ysaÿe’s Third Violin Sonata, Ballade, written for Enescu (1881-1955), is the most concise, but is wide-ranging in scope. According to Yehudi Menuhin, Enescu embodied the breadth of Western violin music which Ysaÿe was trying to mirror in these sonatas: “Enescu’s mind dealt in centuries… wide measures of time and space… his memory held the collected works of all the great composers from Bach to Bartók.” Ysaÿe’s student Josef Gingold argued that of all the sonatas the third represents the closest reflection of Ysaÿe’s own playing style. The work is cast in a single movement, the violin unfolding a musical soliloquy and growing increasingly animated as it leads us into a virtuosic Allegro.

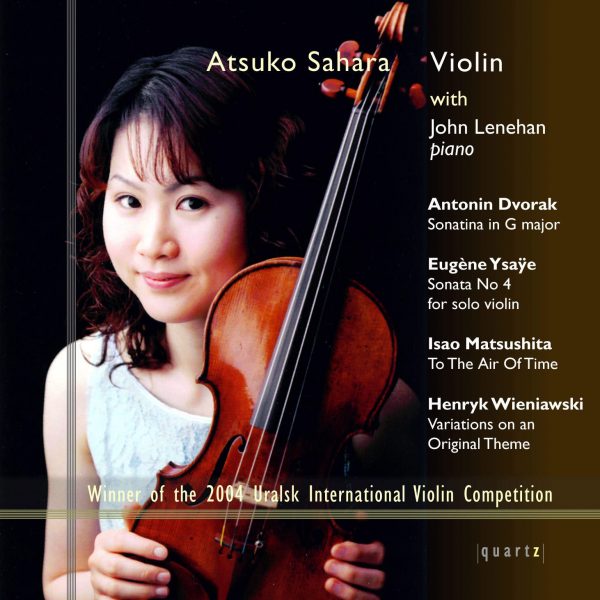

The Sonata No.4, Ysaÿe’s favourite, is dedicated to Austrian violinist-composer Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962). Two of the sonata’s three movements echo those of a Baroque suite: an Allemanda (a stately German dance), and a Sarabanda (a Spanish dance in triple time), both reminiscent of Bach. There follows a Presto in a more fluid, modernist style, but related to the preceding Sarabanda by a persistent motif which is woven into both movements, including the joyous final coda. Kreisler was not renowned as an interpreter of Baroque music, but was adept at writing pastiche, and Ysaÿe acknowledges this in the neoclassical opening movements, and by referring to Kreisler’s Praeludium and Allegro in the style of Pugnani during the Presto.

The Sonata No.5 is dedicated to the Belgian violinist Mathieu Crickboom (1871-1947), Ysaÿe’s most devoted disciple and a member of the Ysaÿe Quartet. The work anticipates Bartók in its use of whole-tones and quarter-tones, as well as contrapuntal devices such as sustained notes commented upon by pizzicato interjections. The ethereal opening movement, L’aurore, evokes the dawn, followed by a Danse rustique with folk-like open harmonies.

Manuel Quiroga (1892-1961) never played the Sonata No.6 owing to the injury which curtailed his promising career, but he is immortalised in its music: a colourful, one-movement habanera conjuring up Quiroga’s native Spain.

Ysaÿe’s Étude posthume was, as its title demonstrates, published after the composer’s death in 1931. He had been suffering so severely from diabetes that his left foot had been amputated. This is a rare recording of the work. As one might expect from “the King of the Violin”, Ysaÿe fills this study with demanding devices intended to stretch the performer’s technique. Yet there is vibrancy, too, in the piece’s arpeggiac texture.

David Oistrakh declared that Ysaÿe’s Six Solo Sonatas are distinguished “by the truest inspiration and originality. At the same time they open up new horizons in the history of violin virtuosity: in them Ysaÿe stands out as the greatest innovator after Paganini.” In common with Paganini, Ysaÿe relished technical virtuosity – as his Étude posthume also demonstrates – but he emphasised this as a means to emotional expression, rather than an end in itself. Ysaÿe argued that: “at the present day the tools of violin mastery, of expression, technique, mechanism, are far more necessary than in days gone by. In fact they are indispensable, if the spirit is to express itself without restraint.”

—© Joanna Wyld, 2018

Track Listing

-

Sonata No.1 Op.27 n1 “a Joseph Szigeti”

- Grave (4:33)

- Fugato (4:20)

- Allegretto poco scherzoso (4:36)

- Finale con brio (2:40) Sonata No. 2 Op.27 n2 “a Jacques Thibaud”

- Obsession (2:27)

- Malinconia (2:54)

- Danse des hombres (4:15)

- Les furies (3:12) Sonata No.3 Op.27 n3 “a Georges Enescu”

- Ballade (6:59) Sonata No.4 Op.27 n4 “a Fritz Kreisler”

- Allemanda (5:37)

- Sarabande (3:16)

- Finale (3:17) Sonata No.5 Op.27 n5 “a Mathieu Crickboom”

- L'Aurore (4:07)

- Dance rustique (5:03) Sonata No.6 op. 27 “a Manuel Quiroga”

- Allegro giusto non troppo vivo (7:21) Étude posthume

- Moderato (3:01)