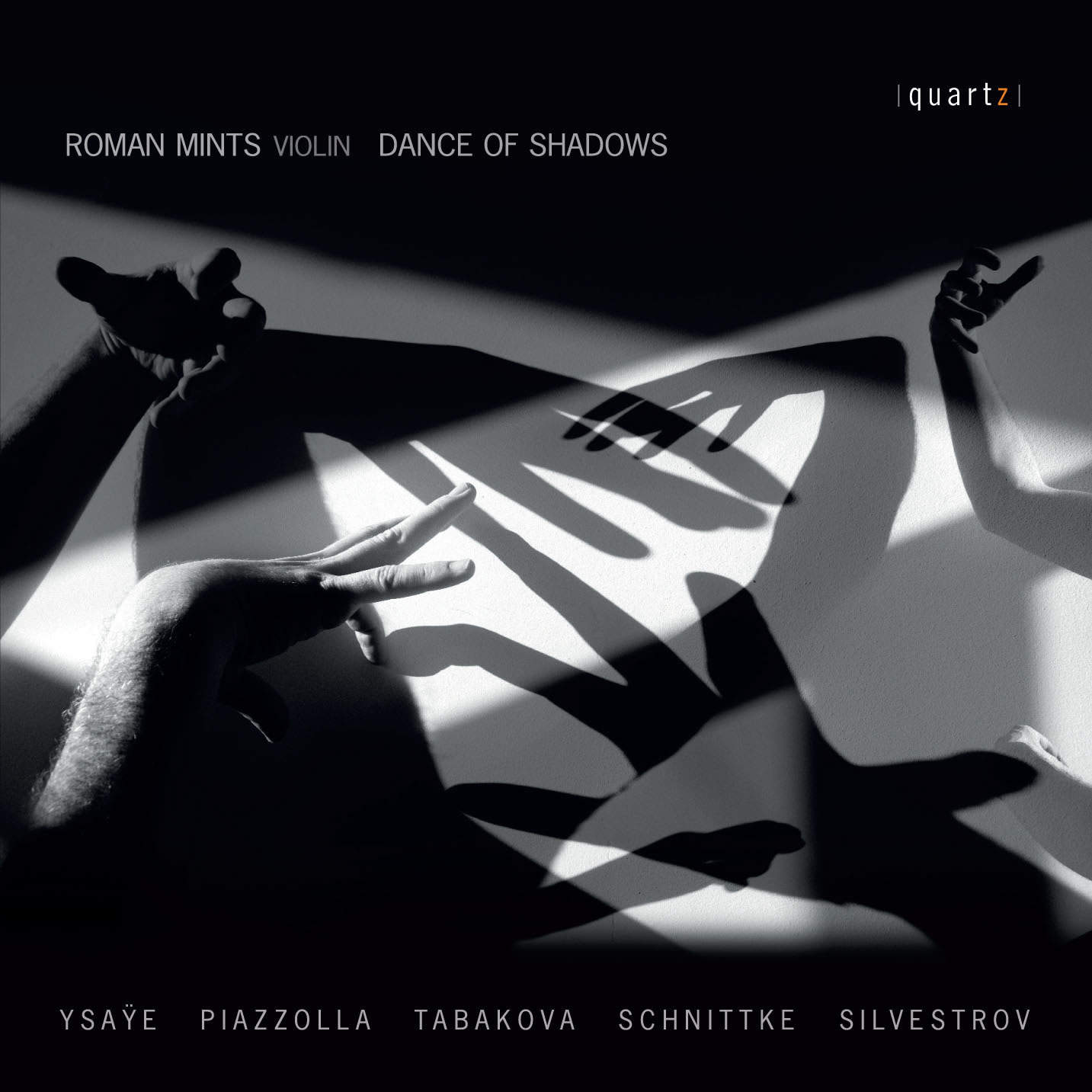

Dance of Shadows

£5.99 – £11.99

EUGENE YSAYE 1858-1931

SONATA OP.27 NO.2 (1923)

ASTOR PIAZZOLLA 1921-1992

TANGO – ÉTUDE NO.2, ANXIEUX E RUBATO (1987)

DOBRINKA TABAKOVA b.1982

SPINNING A YARN (2011)

ALFRED SCHNITTKE 1934-1998

A PAGANINI (1982)

VALENTIN SILVESTROV b.1937

POSTLUDE (1981/1982)

A new release by the multi-award winning Russian violinist Roman Mints. Each piece on this recording has been chosen by the artist for very personal reasons. It includes the notable premiere of Dobrinka Tabakova’s Spinning a Yarn, for violin and Russian Hurdy-Gurdy (kolesnaya lira) written especially by the composer for Roman Mints.

The recording premieres the use of Spatial Orchestration, a concept created by Mints to give the listener a unique understanding of each track. To find the right sound for each piece of music, Roman has used different place settings for the microphone, as well as moving his instrument around the studio, allowing his personal interpretation to enhance the final experience.

About This Recording

Sound recording, which caused such a revolution in the performing arts, has also led inexorably to its crisis. Before recordings existed, there were only rare opportunities to hear any given piece, so comparing performances was no easy matter. A contemporary of Brahms would have been able to hear his symphonies only a few times during his life. Now anyone can listen to any of Brahms’ symphonies with two clicks of a mouse, in hundreds of different versions, without leaving the house. In the past a person would go to a concert expressly to hear a particular work; now he goes so he can tick off yet another interpretation of a work he has heard a hundred times.

Since sound-recording began, the professions of performer and composer have diverged enormously and the performer, not being a genuine creator, naturally enough feels a constant need to prove his existence to himself and to others – and it is recordings that provide the fundamental platform for such proof. Every “self respecting” violinist is determined to leave his version of the concertos of Tchaikovsky, Brahms and Sibelius to posterity and thus over the past century the market has been glutted with recordings of the “gold reserves” of the violin repertoire. (The violin is my personal example; the piano repertoire is of course vastly more extensive.) Given over a hundred interpretations, any possible interest must surely be sated for years to come, if not for ever. Naturally in most of them similar performance decisions have been made, not only because “that’s the way it’s done” but also because it is rather foolish to diverge from the composer’s wishes and the natural flow of the music, simply in an attempt to be original. The last time I heard something new in the third movement of the Tchaikovsky concerto

Khrustevich: what was new was precisely that it was played on the bayan and it struck me that, had such expertise on this instrument existed in Tchaikovsky’s day, he might well have written this music for the bayan – which suits it much better. So now we have reached the point where new recordings of mainstream repertoire are basically of interest only to the performers themselves and their hardcore fans. A few years ago, an executive of one of the largest recording companies told me with horror that the new recording by a well-known violinist of the Tchaikovsky concerto had sold only a comical 500 copies but if my collection includes Oistrakh and Heifetz, how many more recordings could I possibly want? Could there conceivably be anything new to hear in them?

I have been pondering these matters for ages and I have concluded that to have a moral right to make a recording it must be one I would want in my own collection. I need to be sure I am offering the listener something that no-one has offered before. Up to a point this can be accomplished by performing new music – that’s clearly the easiest solution, but contemporary classical music is going through its own crisis – a subject large enough for a number of books, most of which have already been written by the Moscow composer Vladimir Martynov. Basically there is just not enough good new music to occupy a performer as hungry for pieces to perform as I am. Then there are further possibilities afforded by rarely-performed pieces and finally, by well-known compositions where I can find something new to say.

This present disc contains a number of pieces, each close to my heart for very personal reasons. I will mention a few of them here.

The story of this album begins during my college days, when I was studying with my teacher Professor Felix Andriyevsky. We were both working on the interpretation of Eugene Ysaye’s Sonata No.2, a piece that I had never been really happy with in my performances. Over the years I would occasionally return to it (at home, not in concerts), trying to pin down something specific I felt but could never manage to express on the violin – something I had always also found lacking in the interpretations of other violinists, of which I had listened to many. I was particularly exercised by the beginning of the first movement, Obsession. Ysaye famously quotes Bach’s Preludio from the Partita No.3; this is the soil from which the obsession of the first movement grows and at the end, Bach’s theme mingles with Ysaye’s own material. It was obvious to me that the appearances of the “delusion” – the Bach theme – should create the feeling of delirium or hallucinations in the mind of the protagonist, who is throughout in a state of extreme excitement, but making this happen without using “special effects” seemed impossible. Then one day it came to me that instead of fruitlessly slogging away trying to create the effect of sounds coming from somewhere far off, it was the source of the sound itself that needed to move – and each time, move to a different place. This could be done using a montage effect, rather like a cinematic montage. I put my idea to the sound engineer Maria Soboleva and thanks to her talent and expertise, we finally got there in October 2012 in Studio No.1, GDRZ in Moscow. I moved around the studio, clambered up onto the balcony and the choir stalls and so on and managed to produce the exact effect I had heard in my mind’s ear for many years. I should add that while working on this sonata, the piece became so much “mine” that I allowed myself here and there to interfere with the written notes. I hope I will be forgiven this sin; as everyone knows, solo violin playing always involves a certain freedom with the composed text.

As soon as I got this idea for performing the Ysaye Sonata, I realised I should adopt the same approach with another piece in my repertoire, Schnittke’s A Paganini. This piece which I think encapsulates the myth of Paganini much more effectively than the music of the “Devil’s violinist” himself, explodes at its climax with a collage from Paganini’s Caprices. Since I feel this collage represents another sort of delirium, using this “spatial orchestration” (as I called the method) seemed entirely appropriate.

Dobrinka Tabakova’s piece Spinning a Yarn, for violin and kolesnaya lira (Russian hurdy-gurdy) is for me the most personal of these pieces, since Dobrinka wrote it as a present for my two then unborn twins, Eva and Ilya. The kolesnaya lira is a simple version of the western hurdy-gurdy; in Russia it was most often used to accompany the singing of spiritual poetry by beggars and vagrants. For one of my birthdays my fiancée Anna gave me a kolesnaya lira specially made for me by the Moscow craftsman Alexander Zhukovsky and on this recording I play both instruments using multi-tracking.

There were two starting-points in preparing Piazzolla’s Etude No.2: firstly the composer’s markings Anxieux et rubato, and secondly the many recordings made by Piazzolla himself, in which he never exactly follows his own text. We placed the microphone so as to produce a more “pop” than “classical” sound – whatever that means.

The programme ends with Silvestrov’s Postlude. What interests me with this composer is that he writes very precise directions for the interpretation he wants. Every note carries a dynamic and rhythmic mark; this method might be a result of his early “serial” period. After several attempts to faithfully observe all the written markings, you attain a new level of rubato playing – achieving freedom through complete self-control. Since the composer himself characterises his music as an echo of something already written (“My music is a response to an an echo of what already exists”), in this recording we placed the violin as far away as possible in order to create the right effect.

For each piece, then, we tried to find the right sound, not only through how I played, but also by using different placings of the microphone in each piece. During the editing process I realised we had accomplished what we wanted when our editor Elena Sych asked me whether I had actually used different instruments in the various pieces.

© Roman Mints, 2014Translated by Robert Thicknesse

EUGENE YSAYE: VIOLIN SONATA IN A MINOR, OP.27, NO.2 (1923)

Once his performing days were behind him, Belgian violinist-composer Eugene Ysaye set about writing his Six Sonates pour violon seul, Op.27, inspired by a performance of Bach’s Sonata for solo violin in G minor (BWV1001), given by Joseph Szigeti. Ysaye, who had received no formal training as a composer, produced sketches for all six works in only 24 hours. The sonatas display Bach’s influence, as well as communicating something of the spirit of each of their young dedicatees, who were all violinists; some were composers, as well.

The second of the Op.27 sonatas is dedicated to the French violinist Jacques Thibaud (1880-1953), who always began his practice routine with the “Preludio” from Bach’s Partita No.3 in E major (BWV1006). Ysaye alludes to this in his sonata’s “Prelude”, called “Obsession”, in which the famous theme from Bach’s Partita vies for attention with the “Dies irae” plainchant from the Mass – a motif which goes on to recur throughout the sonata. The Bach phrase and the “Dies irae” chant share the same opening notes – perhaps why the chant suggested itself to Ysaye as he composed the work.

DOBRINKA TABAKOVA: SPINNING A YARN (2011)

Composer Dobrinka Tabakova writes: “Spinning a yarn, also an expression meaning to “tell an elaborate story”, grew quite physically from the nature of playing the hurdy-gurdy. The turning of the wooden wheel brought images of a spindle and spinning wheel and the fantastical world of the Brothers Grimm tales. This became the inspiration of the work – the violin melody is guided by the pulse of the hurdy-gurdy, spinning a phrase which gets passed from one instrument to the other. It’s a musical story for its dedicatees – the Mints twins and family.”

ASTOR PIAZZOLLA: éTUDE NO.2 (1987)

Astor Piazzolla studied with Alberto Ginastera and then with the great Nadia Boulanger. With characteristic insight, it was Boulanger who recognised where Piazzolla’s real passions lay. In 1954 she urged him to focus on the tango rather than on purely classical forms, observing: “Here you have the real Piazzolla; Astor, be true to him”.

In exploring and communicating the music of his native Argentina, Piazzolla was also recording and celebrating its essence, much as Bartók and Gershwin drew upon the folk and jazz styles of their countries and translated them into a classical context. Perhaps inevitably, there have been those who wish to demarcate the line between “classical” and “popular” too rigidly, who have rather dismissed Piazzolla’s music as “light”. One anecdote tells us that, in the 1950s, when Piazzolla was conducting a symphony, a member of the orchestra said, “I assume you are nothing to do with this Piazzolla who plays tangos.” For that musician, the worlds of the tango and the symphony were mutually exclusive; but not for Piazzolla and the repertoire is the richer for it.

In fact, much of Piazzolla’s music is not “light” at all; it is gritty and uncompromising, and provoked many traditionalists to object to his modern treatment of the tango. Amid these criticisms coming from opposite directions, Piazzolla, stood firm and his unique approach breathed new life into a genre that had risked becoming stale.

The Six études tanguistiques for solo flute or violin date from 1987; the second is the longest of the set. As Roman Mints describes, it is marked “Anxieux e rubato” (“Anxiously and with rubato”) and is characterised by its shifts between sustained notes and nervous, fluttering gestures, as well as the rhythmic freedom afforded by the “rubato” marking.

The movement which follows, entitled “Danse des ombres” – “Dance of shadows” – continues this mixture of different idioms, but with a distinct mood as befits its title. On the score, the subtitle “Sarabande” is written near the main theme, which is followed by a set of variations, including a Musette which contrasts with the opening pizzicati. The upper voice of the main chord progression is the “Dies irae” theme, this time harmonized in G major, presenting a different facet of that theme’s harmonic implications.

In the finale, however, Ysaye unleashes “Les furies” in a movement taut with intense energy, using the “Dies irae” theme scattered across the movement, and releasing the full rhetorical force of the violin. Ghostly “sul ponticello” writing (bowing near the bridge) provides moments of contrast, and the use of the tritone is reminiscent of famous scordatura violin music from Biber to Paganini to the Danse macabre of Saint-Saens.

The violinist David Oistrakh declared that Ysaye’s Op.27 solo sonatas are distinguished “by the truest inspiration and originality. At the same time they open up new horizons in the history of violin virtuosity: in them Ysaye stands out as the greatest innovator after Paganini. In common with Paganini, Ysaye relished technical virtuosity; but he emphasised that this is a means to emotional expression, arguing: “at the present day the tools of violin mastery, of expression, technique, mechanism, are far more necessary than in days gone by. In fact they are indispensable, if the spirit is to express itself without restraint.”

ASTOR PIAZZOLLA: éTUDE NO.2 (1987)

Astor Piazzolla studied with Alberto Ginastera and then with the great Nadia Boulanger. With characteristic insight, it was Boulanger who recognised where Piazzolla’s real passions lay. In 1954 she urged him to focus on the tango rather than on purely classical forms, observing: “Here you have the real Piazzolla; Astor, be true to him”.

In exploring and communicating the music of his native Argentina, Piazzolla was also recording and celebrating its essence, much as Bartók and Gershwin drew upon the folk and jazz styles of their countries and translated them into a classical context. Perhaps inevitably, there have been those who wish to demarcate the line between “classical” and “popular” too rigidly, who have rather dismissed Piazzolla’s music as “light”. One anecdote tells us that, in the 1950s, when Piazzolla was conducting a symphony, a member of the orchestra said, “I assume you are nothing to do with this Piazzolla who plays tangos.” For that musician, the worlds of the tango and the symphony were mutually exclusive; but not for Piazzolla and the repertoire is the richer for it.

In fact, much of Piazzolla’s music is not “light” at all; it is gritty and uncompromising, and provoked many traditionalists to object to his modern treatment of the tango. Amid these criticisms coming from opposite directions, Piazzolla, stood firm and his unique approach breathed new life into a genre that had risked becoming stale.

The Six études tanguistiques for solo flute or violin date from 1987; the second is the longest of the set. As Roman Mints describes, it is marked “Anxieux e rubato” (“Anxiously and with rubato”) and is characterised by its shifts between sustained notes and nervous, fluttering gestures, as well as the rhythmic freedom afforded by the “rubato” marking.

DOBRINKA TABAKOVA: SPINNING A YARN (2011)

Composer Dobrinka Tabakova writes: “Spinning a yarn, also an expression meaning to “tell an elaborate story”, grew quite physically from the nature of playing the hurdy-gurdy. The turning of the wooden wheel brought images of a spindle and spinning wheel and the fantastical world of the Brothers Grimm tales. This became the inspiration of the work – the violin melody is guided by the pulse of the hurdy-gurdy, spinning a phrase which gets passed from one instrument to the other. It’s a musical story for its dedicatees – the Mints twins and family.”

ALFRED SCHNITTKE: A PAGANINI (1982)

Alfred Schnittke began his musical studies in Vienna, where his exposure to Austro- German styles would have a lasting impact on his own compositions. On his return to Russia, Schnittke studied at the Moscow Conservatory, and has since attributed his “polystylism” to these years, during which he filled in the gaps in his musical knowledge. In The Rest Is Noise, Alex Ross describes it this way: “A master ironist, he developed a language that he called “polystylistics”, gathering up in a troubled stream of consciousness the detritus of a millennium of music.”

Schnittke’s polystylism is characterised by the distinctive use of music from earlier eras, much as Charles Ives had with his Symphony No.2 (1897-1901), and as Berio did in his Sinfonia of 1968-9. So it was that Schnittke wrote works such as Moz-Art a la Haydn (1977), in which he humorously parodies both composers as well as paying tribute to them. Similarly, A Paganini (1982) is a portrayal of the Paganini myth, drawing upon the full gamut of virtuosic violin music. The piece was composed to coincide with Paganini’s bicentenary, and was written for the former winner of the Paganini Competition, Oleh Krysa, who had won the prize in 1963. The result is a set of variations with two cadenzas, with the main theme alluding to “Folia”, one of the earliest and most widely-disseminated themes in Western music. There are further references to composers as various as Bach, Rachmaninov and Berg. Schnittke organises this wide-ranging material into an almost diabolical postmodern collage, offering both an homage to, and commentary upon, the rather fantastical nature of Paganini’s reputation as devilishly skilled violinist. Musicologist David Fanning argued that, in so doing, Schnittke treated such earlier composers “with the detached bemusement of a visitor from outer space confronting an artifact from a dead civilization.” The effect is a warped, distorted version of something recognisable. In the composer’s own words: “I set down a beautiful chord on paper – and suddenly it rusts.”

VALENTIN SILVESTROV: POSTLUDE NO.2 FOR SOLO VIOLIN (1981-1982)

Ukrainian composer Valentin Silvestrov was born in Kiev in 1937, and played a key role in forming the avant-garde movement there. However, Silvestrov’s style has evolved into what he calls “meta music” or “metaphorical music”, embracing both lyricism and stillness in a style that has been likened to Mahler. Silvestrov has insisted that pursuing his own voice, rather than musical trends, is a crucial aspect of his compositional approach: “I must write what pleases me and not what others like, not what the age dictates to me. Otherwise I am at the mercy of an economic cycle that cripples the imagination. I must seek beauty.” The hushed, slowly-unfolding nature of the solo violin Postlude – the second work in a set of three, for different instruments – possesses an ancient, timeless quality. The violin’s longbreathed lines are commented upon by pizzicato punctuation. The effect is of stillness, creating a deeply contemplative soundworld – one that reflects Silvestrov’s statement that: “I (and not I alone) sensed a hunger for silence.”

© Joanna Wyld, 2014

Track Listing

-

Eugene Ysaye

- Sonata Op 27 No 2 (i) Obsession | Prelude

- Sonata Op 27 No 2 (ii) Malinconia

- Sonata Op 27 No 2 (iii) Danse des Ombres | Sarabande

- Sonata Op 27 No 2 (iv) Les furies Astor Piazzolla

- Tango - Etude No 2: Anxieux e rubato Dobrinka Tabakova

- Spinning a Yarn Alfred Schnittke

- A Paganini Valentin Silvestrov

- Postlude

Press Reviews

“The Moscow-born violinist Roman Mints, who deserves to be better known in the UK, introduces new or unfamiliar solo works in this fascinating recital disc. First off is the earliest of the works, which has obsessed Mints since college days: Ysaye’s Sonata in A minor(1923), a fiercely virtuosic work inspired by Bach’s G minor sonata. However much the work may once have eluded him, Mints plays it with conviction and insight here. A melancholy work by Dobrinka Tabakova (b.1980), Spinning a Yarn, uses a hurdy gurdy too, and draws on the notion of storytelling. Schnittke’s idiosyncratic tribute to Paganini, a Piazzolla tango – Etude No. 2, Anxieux e rubato – and Postlude by Valentin Silvestrov make up this varied and often haunting disc.” —THE OBSERVER ****