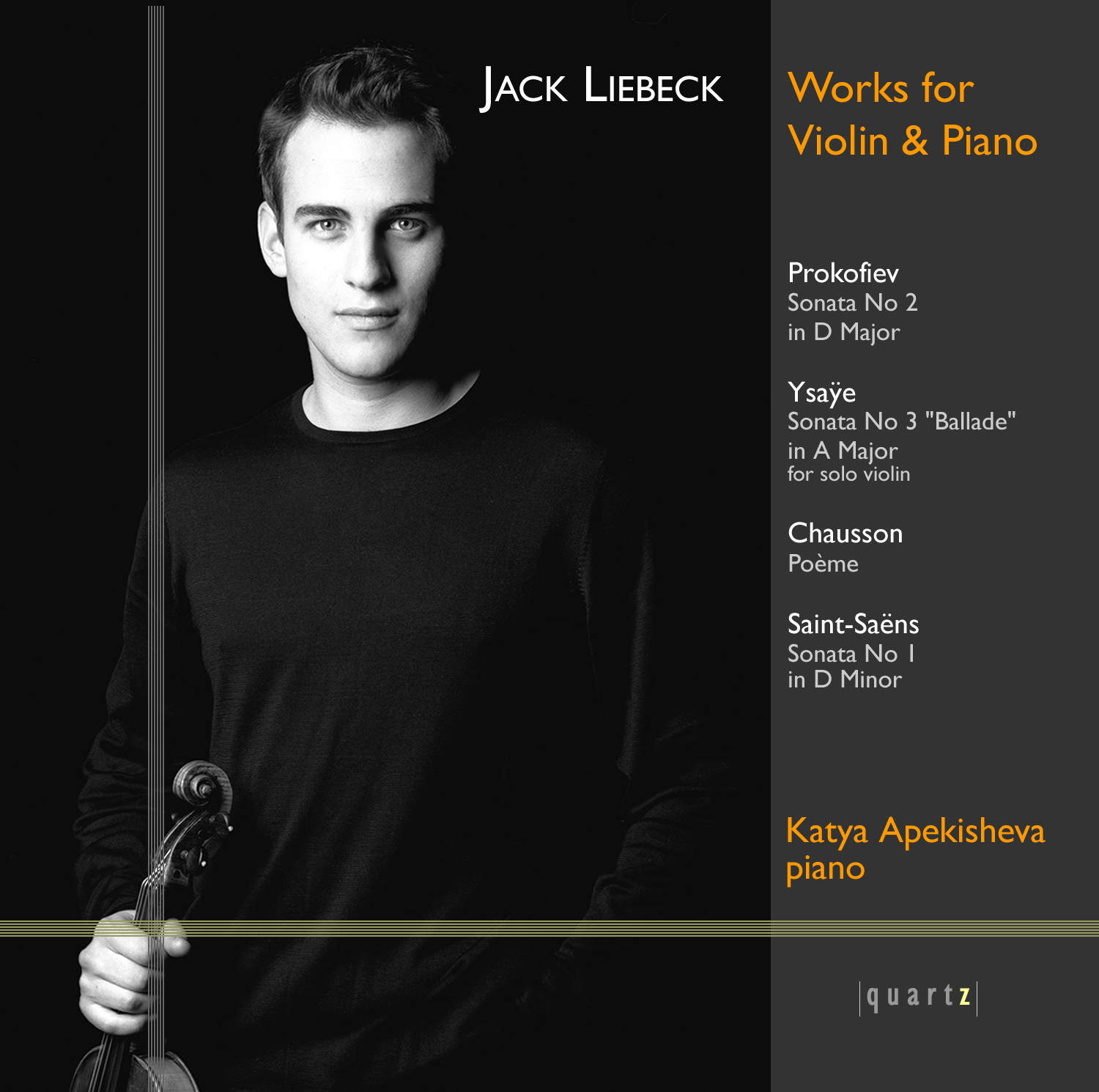

Works for Violin & Piano

Price range: £4.99 through £11.99

SHORTLISTED FOR A CLASSICAL BRIT AWARD 2005

Prokofiev

Sonata No. 2 in D Major, Op. 94a

Ysaye

Sonata No. 3 in D Minor “Ballade” for solo violin

Chausson

Poème

Saint-Saëns

Sonata No 1 in D Minor, Op 75

With Katya Apekisheva – Piano

The debut disc by one of the most talented and acclaimed young violinists to emerge in recent years. Liebeck has established an international reputation for mature, intense and virtuosic performances and this disc of early 20th Century works demonstrates these characteristics in abundance. Partnered here by the virtuoso, award-winning pianist, Katya Apekisheva, this is duo playing of the highest calibre.

About This Recording

In 1943, Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) was evacuated, along with many other prominent artists, to Alma-Ata (Almaty) in modern-day Kazakhstan while the Soviet army fought against the Germans in the West. It was here that he wrote his Sonata for Flute and Piano Op 94 which, at the suggestion of David Oistrakh, he transcribed the following year for violin. The amount of revision needed was minimal and indeed the piano part is exactly the same in both versions.

The Sonata is in stark contrast to the huge upheaval that was taking place on the other side of the country and Prokofiev himself described the work as “perhaps inappropriate at the moment, but pleasant”. The key of D Major is perhaps a conscious reference to the Classical Symphony and certainly the Sonata follows the classical model closely, even incorporating all elements of the standard first-movement sonata-form structure although the boisterous Russian finale has more in common with later models. Prokofiev was reputedly inspired to compose the Sonata after hearing the French flautist Georges Barrere, one of the great exponents of 19th Century French flute music as well as the dedicatee of Edgar Varese’s experimental Density 21.5 and it is perhaps appropriate that he should have been the motivating force behind this work which harks back to earlier forms and yet is very much of its time.

The violinist Eugene Ysaye (1858-1931) was held in high esteem by his Parisian contemporaries as a powerful interpreter of their works. These famous figures included Saint-Saëens, Debussy, Franck and Chausson who all dedicated works to him (indee Chausson’s Poeme was written for Ysaye).

As he was primarily a performer, Ysaye not compose a large catalogue of works and almost all of them were violin pieces. Ysaye’s six solo violin sonatas were inspired by the young Joseph Szigeti’s performance of a Bach solo sonata in 1923. Ysaye is said to have been so inspired that he immediately locked himself away for twenty four hours and emerged with all six in sketch form. Each sonata was dedicated and tailored to a violinist of his time; Szigeti, Thibaud, Enesco, Kreisler, Crickboom and Quiroga. The First and Second Sonatas follow a similar movement structure to Bach’s solo Sonatas and Partitas. Ysaye even quoted the E major Partita in his 2nd sonata (“Obsession”) symbolising and perhaps teasing Jacques Thibaud about his obsession with its opening.

By the Third Sonata (featured here), Ysaye ideas started to move more into his own unique and personal sound world with more chromaticism and free-flowing movement. The sonata is dominated by a fiery and distinctive main thematic idea that develops right until the very end of the piece. He managed to combine this idea with many different episodes of colour and figuration in a way that only a musician with intimate knowledge of the mechanics and capabilities of the violin could. Technically very demanding though the piece is, it is so well tailored to the nature of the violin that it is very playable and has become one of the staples of the violin repertoire. JL.

Ernest Chausson (1855-1899) came to music relatively late in life and was often considered something of an outsider, partly by virtue of his relatively well-off background which meant that he was financially independent throughout his life but also for purely musical reasons.

His music bears the hallmarks of many of the great influences of his day, including Franck, Massenet and Wagner but also exhibits the outcome of his own personal interests and explorations. Towards the end of his life, Chausson became increasingly interested in Russian literature and the work of the Metaphysical poets and the Poeme is based on a short story by Turgenev. Originally titled “Le chant de l’amour triomphant: Poeme symphonique pour violon et orchestre” it was subsequently reduced to “Poeme pour violon et orchestre” and finally simply “Poeme”.

The Poeme was written for and dedicated to the man who gave its premiere, Eugene Ysaye Although the Poeme was written for one of the greatest virtuosos of his day, it is essentially lyrical in style and focuses on emotional intensity rather than technical pyrotechnics, an approach that reflected Ysaye view that virtuosity should never be an end in itself but, rather, a valuable tool in the violinist’s overall technique. It is seamlessly constructed in one movement and demonstrates Chausson’s ability to combine complete command of form and structure while allowing the music to sound freely rhapsodic and lyrical.

Of Chausson, one contemporary wrote “all his works exhale a dreamy sensitiveness which is peculiar to him. His music is constantly saying the word ‘cher’”.

In common with his younger contemporary Fauré chamber music runs across Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) sizeable (and now neglected) output – from the often bravura ensemble works of the 1860s and ’70s to the autumnal sonatas and character pieces of his last years. In 1885, his First Violin Sonata was written for and dedicated to Martin Marsick – teacher of, among others, Thibaud, Enescu and Flesch. The influence of Liszt is evident in the thematic transformation which operates throughout the piece, as also in the linking of the movements into two complementary pairs – a procedure which Saint-Saëns repeated only in his ‘Organ Symphony’, written in memory of Liszt the following year.

The darkly sensuous idea which opens the first movement has a fluid, rhythmic profile – in marked contrast with the wistful second theme, which retains its formal outline throughout. There is no development as such, but a modified reprise of the two themes, followed by a sombre coda which tapers away in a poetic transition to the Adagio. The main melody, a beautifully-judged dialogue, treads a fine line between sentimentality and pathos typical of Saint-Saëns. It twice alternates with a more impulsive (though related) idea, and closes in a mood of tranquil tenderness.

The Mendelssohnian scherzo evolves almost entirely from the tripping five-bar phrase with which it begins. Note how, in the brief trio section, the piano continues the underlying rhythm while the violin derives from it a more songful melody. A curtailed reprise, then a passage of pensive anticipation – leading into the finale. The main theme is a brilliant moto perpetuo, culminating in a high-flown melodic gesture. As in the opening movement, these ideas are modified rather than developed as such – working up to a coda which effectively integrates the two and rounds off the whole work in a stream of exhilarating passagework.

Copyright: Richard Whitehouse, 2003

Track Listing

-

Sergei Prokofiev

- Violin Sonata No 2 in D Major Op 94a (i) Moderato

- Violin Sonata No 2 in D Major (ii) Scherzo: Presto

- Violin Sonata No 2 in D Major (iii) Andante

- Violin Sonata No 2 in D Major (iv) Allegro con brio Eugene Ysaye

- Sonata No 3 in D minor (Ballade) for solo violin Ernest Chausson

- Poeme Camille Saint-Saens

- Violin Sonata No 1 (i) Allegro agitato

- Violin Sonata No 1 (ii) Adagio

- Violin Sonata No 1 (iii) Allegro moderato

- Violin Sonata No 1 (iv) Allegro molto