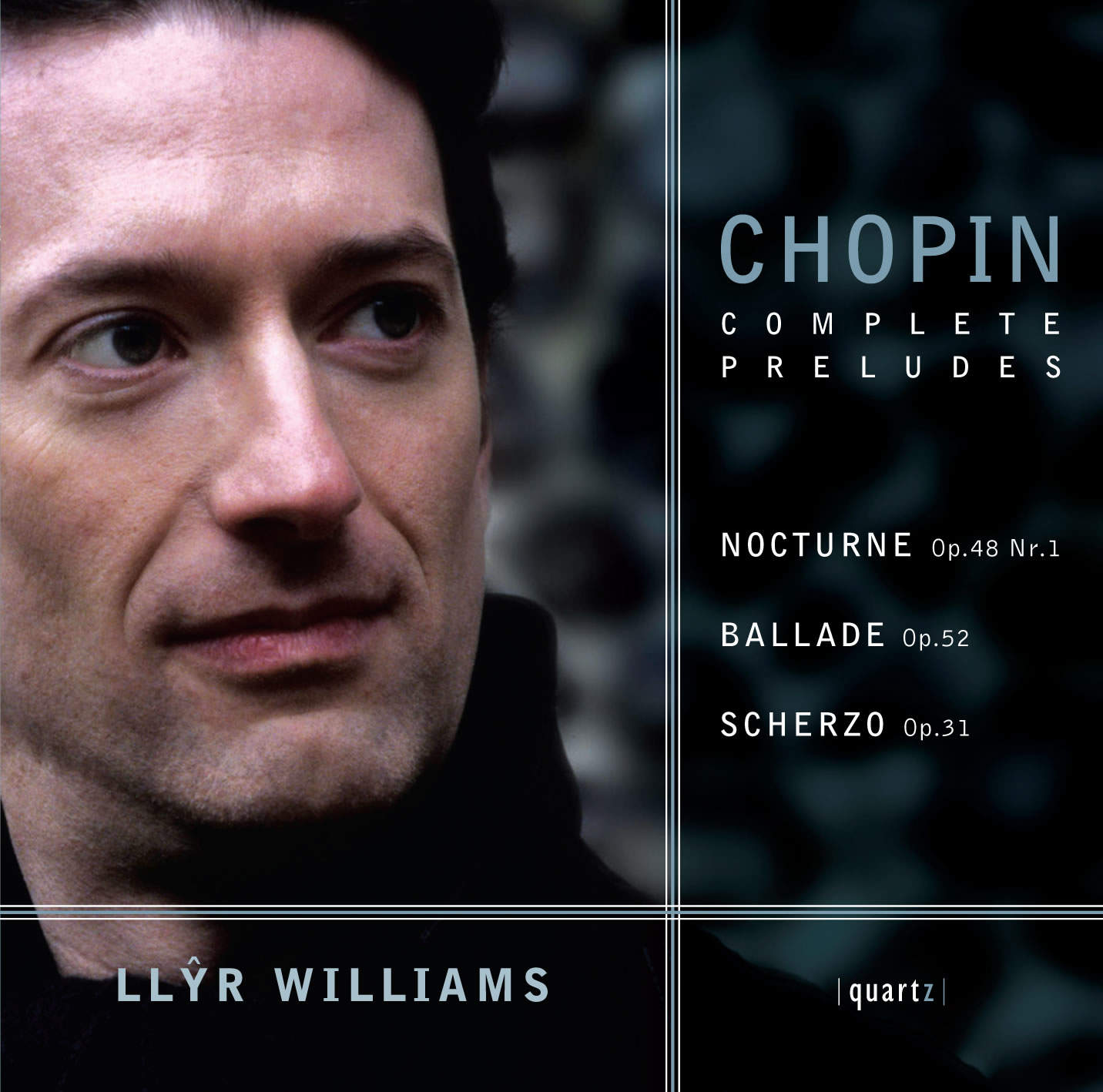

Chopin – Complete Preludes

Price range: £4.99 through £11.99

FREDERIC CHOPIN – COMPLETE PRELUDES

Nocturne, Op. 48 No. 1

Ballade Op. 52

Scherzo Op. 31

Llyr Williams – Piano

“Yesterday, to judge from the tumultuous ovation that followed his dazzling performance of Chopin’s opus 28 Preludes, free of both perfume and rhetoric, then history repeated itself. Certainly, I believe that a performance of these 24 miracles of miniaturism which has more clarity, transparency and economy than Williams’s interpretation is just about unthinkable.” —The Glasgow Herald

About This Recording

As we begin listening to the opening bars of the C major prelude, no.1 from Op.28, Chopin immediately invites us to reflect on a bundle of contradictions. This piece in outward appearance seems to fulfil the requirements of what might be expected from the Prelude as genre – its musical gestures are “opening” ones, establishing a clear tonality and articulating it by means of seemingly conventional arpeggio figures. Prelude to what however? In contrast to earlier usages of the term in keyboard music, whether in conjunction with a fugue or as the opening movement in a series of dances (the Baroque Suite), Chopin’s Op.28 no.1 merely preludes other preludes. Contradictions are manifest at the micro-level in addition. Chopin’s arpeggio figurations are ambiguous in that it is not clear whether the main melodic voice is in the top finger or in the thumb of the right hand – the listener will perceive this as a subtle but continuous shifting of emphasis between the two parts – while the almost orgasmic rush of passion at the piece’s climax seems entirely at odds with its basically simple harmonic outline and general brevity.

Certain of the preludes are embodiments of the Romantic fragment, itself a contradictory literary form which is both complete in itself and simultaneously pointing outside itself. Take, for instance, no.23, a highly original piece which founds itself not on melody or rhythm, but rather on texture and prolongs itself by continually expanding the piano’s register. In the penultimate bar Chopin disturbs the piece’s harmonic basis by introducing a foreign Eb which is kept hanging until the end. Within conventional harmonic grammar, this note demands resolution onto another chord – something withheld by Chopin and thus rendering the piece distinctly inconclusive (a device which certainly was not lost on a much later generation of composers).

The biggest contradiction of all however concerns the issue of programming. Although we know for certain that Chopin himself never performed Op.28 as a complete entity, the whole work is now constantly played the world over as one of the pinnacles of the romantic piano repertoire. While running through the gamut of all the major and minor keys in a systematic way does not in itself guarantee unity. I suggest that the listener will begin appreciating how the preludes interact with one another if the totality is played – this process of interaction often manifesting itself in unexpected places. A case in point is the ending of no.2 – a morbid piece which not so much states its tonality but rather searches for it. In the closing bars, the music takes on a more definite profile as we hear a chorale-like phrase which features repeated B’s in the uppermost voice.

This same phrase, identically harmonised, is then taken up – grand and confident – as the starting point of the ninth prelude. Also note how the B from the end of no.2 continues to be prominent in no.3. Indeed, many of the early preludes gravitate in some way towards B, a process subtly at odds with their ascending key sequence. No.4 features constant alternation between B and its neighbour, C, while no.5 reverses the process – oscillating between B and its lower neighbour Bb.

Another instance where one only grasps fully the richness of Chopin’s palette when the preludes are set side by side involves nos. 14 and 15. No.14 is a menacing, rather disturbing piece, entirely in the bottom to middle registers of the keyboard, only hinting at melodic strands before disintegrating. It is immediately swept aside by the cantilena of no.15 where the pianist has to assimilate the roles of operatic diva and her accompanist. However, the middle section of this piece returns us to the same register and again only half-suggested melody (it has been said that this music evokes the chanting of monks at Valdemosa on Majorca where Chopin composed most of Op.28)

Elsewhere, playing the complete preludes can sometimes be more of a problem then an asset. How does one follow no.18 for instance, with its cataclysmic descent into the abyss? After such a powerful conclusion it is difficult to bring oneself to begin no.19.

Similarly, quixotic changes of mood sometimes occur with such quick-fire rapidity that it makes an issue of the need to maintain continuity. No.10 is one of the most mercurial of all the preludes – entirely constructed from the alternation of a strange descending scale figure and a fragment of a chordal figure – all taking place in less than half a minute. The following prelude on the other hand – bright and radiant no.11 – seems suddenly to inhabit a different world altogether.

Nevertheless, when listening to the totality of Op.28, one is urged to appreciate not only the extraordinarily large spectrum of Chopin’s imagination, but also the way the preludes reflect and refract one another.

Track Listing

-

Frederic Chopin

- Prelude in C major - Agitato

- Prelude in A minor - Lento

- Prelude in G major - Vivace

- Prelude in E minor - Largo

- Prelude in D major - Allegro molto

- Prelude in B minor - Lento assai

- Prelude in A major - Andantino

- Prelude in F sharp minor - Molto agitato

- Prelude in E major: Largo

- Prelude in C sharp minor: Allegro molto

- Prelude in B major: Vivace

- Prelude in G sharp minor: Presto

- Prelude in F sharp major: Lento

- Prelude in E flat minor: Allegro

- Prelude in D flat major: Sostenuto

- Prelude in B flat minor: Presto con fuoco

- Prelude in A flat major: Allegretto

- Prelude in F minor: Allegro molto

- Prelude in E flat major: Vivace

- Prelude in C minor: Largo

- Prelude in B flat major: Cantabile

- Prelude in G minor: Molto agitato

- Prelude in F major: Moderato

- Prelude in D minor: Allegro appassionato

- Nocturne Op. 48 No. 1

- Ballade Op. 52

- Scherzo Op. 31