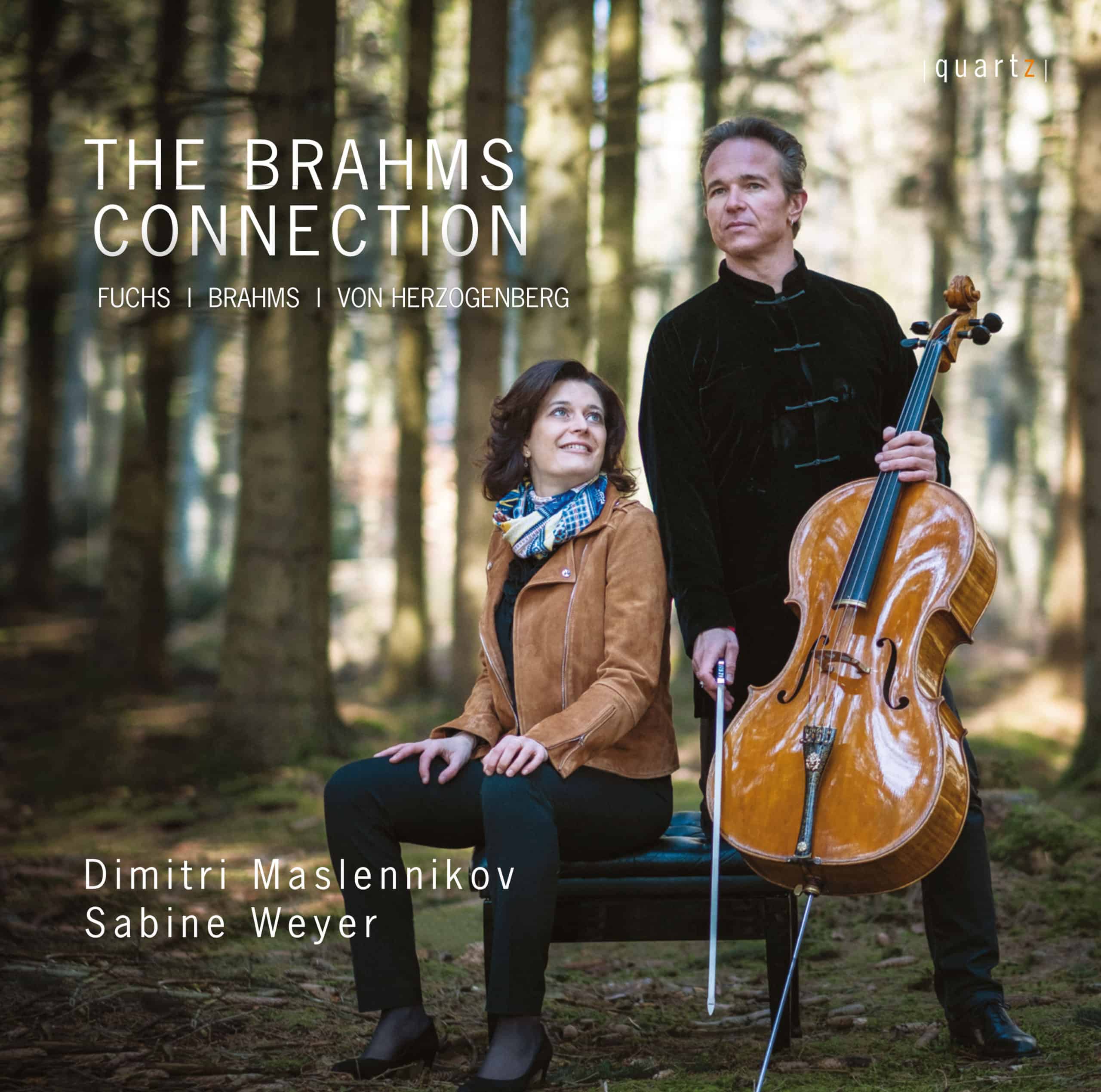

The Brahms Connection

Price range: £7.99 through £16.99

This collection of three Sonatas for cello and piano comprises works that appeared between 1865-6 and 1886 by composers who were colleagues. If their personal association varied between genuine friendship and mere acquaintance, each became a significant figure in the era approaching the zenith of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Praised as “one of the most important young pianists of today” by International Piano, Sabine Weyer showed an exceptional musical talent since her earliest childhood. Following her initial training at the Conservatoire of Esch Alzette in Luxembourg, she studied at pianistic schools in France, Belgium, the United Kingdom under the guidance of, amongst others, Bernard Lerouge (CRR Metz, France), Vassil Guenov (Belgium), Aleksandar Madzar (Koninklijk Conservatorium Brussel, Belgium), Rustem Hayroudinoff (Royal Academy of Music, London, UK). Since 2015 Sabine Weyer has been professor for piano at the Conservatoire de la Ville de Luxembourg, fulfilling her desire to pass on musical knowledge to younger generations. As a pedagogue, she has been invited to teach at masterclasses abroad including at the Scriabine Summer Academy in Italy, the Beijing Normal University in China, and the European Summer Music Academy in Djakova/Kosovo. Dimitri Maslennikov began his musical studies at the age of five. At 11 years old, he won the International Soloists Competition in Moscow and the Czech International Competition in Prague. He was a winner of the Tchaikovsky Competition and the Rostropovitch Competition. At the age of 14, he received a three-year scholarship from the French government to study at the Paris Conservatory where he attained First Prize. He has been championed by maestro Christoph Eschenbach and has performed with the NDR Hamburg Orchestra, the Bamberger Symphoniker, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and the Philadelphia Orchestra, with whom he has made a ‘live’ recording.

About This Recording

The Brahms Connection

ROBERT FUCHS Sonata No.1 in D minor Op.29 (1878)

JOHANNES BRAHMS Sonata No.1 in E minor Op.38 (1865)

HEINRICH VON HERZOGENBERG Sonata No.1 in A minor Op.52 (1886)

This collection of three sonatas for cello and piano comprises works that appeared between 1865–6 and 1886 by composers who were colleagues. If their personal association varied between genuine friendship and mere acquaintance, each became a significant figure in the era approaching the zenith of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

In discussing their music in chronological order, our commentary begins with the Sonata in E minor by Johannes Brahms. The popular image of Brahms is of a confirmed bachelor, set in his ways, his rented accommodation in his adopted city of Vienna naturally reflecting his outlook on the world. Once, when asked about his life, he replied: ’I have attended no schools or institutions for musical culture. I have embarked on no travels for purposes of study. I have received no instruction from eminent masters. I am the incumbent of no public offices, and I hold no official positions.’

If Brahms lived a simple -– though hardly monastic – life, it ran alongside a vibrant inner creativity which expressed itself through his music, from which he earned a great deal of money. Although he was by no means miserly in his dealings with close friends, his estate at his death in 1897, most of which he bequeathed to the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien (Society of the Friends of Music in Vienna), amounted to about 400,000 gulden: around €7.5 million in today’s terms.

Brahms first visited Vienna in his late twenties; in 1863 he was appointed conductor

of the Vienna Singakademie. Soon after making the city his home, he struck up a friendship with Joseph Gänsbacher, an amateur cellist who had studied law. He also took singing lessons before becoming a singing teacher himself at the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, becoming professor in 1876 at the time Brahms had been appointed music director of the Society.

Brahms and Joseph Gänsbacher would play chamber music together at Brahms’ apartment, and it was to Gänsbacher that Brahms dedicated his Sonata in

E minor, Opus 38, composed between 1862-65. The first two movements of the Sonata date from 1862, together with an Adagio movement which Brahms withdrew, leaving the Sonata without a slow movement. The surviving finale followed in 1865, the complete Sonata first appearing in print the following year, published by Simrock.

Whatever the work’s provenance, Brahms’ Opus 38 is the finest Cello Sonata to appear since those of Beethoven, the length of time its composition took before the composer was satisfied anticipating the care Brahms took over his First Symphony, which finally appeared in 1876 after 21 years in gestation.

The Cello Sonata’s three-movement structure is unusual for the period. The first movement is by far the most extensive; the pulse is moderate and, uniquely, employs three themes, although not so varied as classical ‘first and second subject’ nomenclature would customarily infer. The music’s rather sombre mood is only lightened somewhat towards the end.

The second movement – a rare Minuet in a Sonata of this period – opens and finally returns as a courteous intermezzo-like dance, affording great contrast to the music of the first movement, and heightened by a Trio section which may appear Schumannesque to some listeners. The Sonata ends – again, rarely – with a mainly fugal finale. It has been pointed out that the subject is virtually the same as one that frequently appears in Johann Sebastian Bach’s Kunst der Fuge, thereby forming one of Brahms’ tributes to the baroque era. However, as if looking back to the first movement, the main subject of the fugue is answered throughout by three countersubjects: Karl Geiringer claimed the initial main theme of the first movement is a reminiscence of the Third contrapunctus from the Kunst der Fuge. Be that as it may, the resultant texture throughout the Sonata’s opening and closing movements is extraordinarily detailed, Brahms’ demands on the players – both technical and musical – being considerable.

It was reported, years after Brahms’ death, that during a private run-through of the Sonata Gänsbacher complained to Brahms that the piano was too loud, and he could not hear his cello: ‘Lucky for you!’, Brahms is said to have replied – a comment which, if true, was surely not meant maliciously: Brahms was noted for his somewhat sarcastic humour. Nonetheless, there is a musical point to be made – the E minor Cello Sonata was the first of Brahms’ seven sonatas for solo instrument and piano. A dozen years were to elapse before a successor appeared (not for cello, that was to come over twenty years later, but the first of his three Sonatas for violin); for Brahms, himself a pianist, the piano in his Sonatas would have assumed equal importance from the start.

Robert Fuchs was fourteen years younger than Brahms, having been born close to the Styrian capital of Graz in 1847. He attended the Vienna Conservatoire where he studied with the legendary Otto Dessoff, among other professors, and by 1875 Fuchs himself was on the staff of the Conservatoire. He eventually became Professor of Composition there, and – in 1893 – Director.

As a teacher, Fuchs was widely admired; such later masters as Mahler, Sibelius, Hugo Wolf, Franz Schmidt, Alexander von Zemlinsky and Franz Schreker all studied with him. Fuchs’ music was much admired by his contemporaries and students as well as by Artur Nikisch, Felix von Weingartner and Hans Richter, but it is claimed the main reason for the later neglect off his music was his unwillingness to promote his own compositions – but many were published, and were therefore available, within a few years of having been written.

Fuchs was known to Brahms as a colleague and as a composer; among several of his works Brahms is known to have particularly praised is the composer’s first Cello Sonata in D minor, published in Leipzig as Opus 29 in 1881, although it had doubtless been written several years earlier. The Sonata is dedicated to the great cellist – and prolific composer – David Popper, ‘in friendship’, with whose pianist wife Sophie Menter (a pupil of Liszt, and later friend of Tchaikovsky) Popper gave the premiere in Vienna. Brahms was present, and praised the work in no uncertain terms. His admiration of the Sonata may have been that it exhibits characteristics now considered as Brahmsian.

If both composers’ approach to composition may have run along similar lines, it must be emphasised that Fuchs’ Sonata contains touches which mark him out individually, not merely as a ‘follower’ of Brahms. We see this in the first of the work’s four movements: from the cello’s quietly extended and broadly-expressive opening theme, with the piano’s fluent accompaniment, a Molto moderato tempo launches this masterly score on its expressive way. The piano’s variant, heard soon after, joins the instruments in fluent dialogue before the tonality falls a semitone to a beautiful stretch of music in D flat major, later rising equally to a powerful statement in E flat major. Fuchs’ fascination with keys semitones apart from the inherent D minor, assists the nature of the music, which grows, expands and flows with a fluidity that is wholly organic and profoundly expressive, before a coda reminiscenza brings the movement to a close.

The second movement, a Scherzo, is more contrasted – not so humorous as being full of life and contained energy, with dance references further lightening the mood. The succeeding Adagio is somewhat shorter than might be expected, but Fuchs’ natural sense of form and expressive balance is admirable in preparing for the finale, Allegro non troppo, wherein the mood, but not character, of such finely- composed music is lightened, bringing this unjustly neglected and fully-imagined masterwork to its conclusion.

The third Sonata in our collection, like the Sonatas by Brahms and Fuchs, also has three movements. It is by the Austrian composer and conductor Heinrich Herzogenberg, who was born (as was Fuchs) in Graz, in 1843. Herzogenbach began his senior studies not in music but in law, philosophy and political science at the university of Vienna. However, the pull of music was too strong, for he later became a pupil of Felix Otto Dessoff.

In great contrast to the lyrical opening of Fuch’s Sonata, Herzogenberg’s work begins with a powerful burst of energy, Allegro 2/4, that carries all before it, rhythmically and melodically, the instruments as one in expressive intensity. A contrasting theme, which we may term the second subject, is almost at once countered by a return to the opening idea following the piano’s quietly rising cadential phrase.

These vivid themes are now explored and developed with intensity, the energy released propelling the music in thrilling fashion until the powerful coda unites the material in magisterial fashion, triumphantly concluding the movement in A minor. The second movement, a flowing Adagio, is uniquely set upon E as its tonal centre – the initial half, in a finely expressive E minor, is an extended song without words, as it were, before the major mode discloses an equally fluent second half – an original tonal innovation that would have earned Brahms’ admiration, more so as the material, subtly developed, reveals its profoundly organic and beautifully expressive origin in music of florid countenance.

E major is the dominant of A, the major mode of which is hinted at from the very beginning of the Allegro finale, subtly constructed in the form of a chaconne, which soon veers between major and minor, with the duple pulse of the entire Sonata maintained throughout various episodes: Allegro, Moderato, Più moderato quasi Andante, Allegro con fuoco (now 6/8), Allegretto, Allegro (now 3/4) – before a brilliant Tempo primo returns us to the initial material, as inspirational as it is fully memorable, ending this outstanding work in a mood of justified triumph.

Robert Matthew-Walker © 2022

Track Listing

- Sonata No.1 for cello & piano in D minor Op.2: I. Molto moderato

- Sonata No.1 for cello & piano in D minor Op.2: II. Scherzo: Allegro

- Sonata No.1 for cello & piano in D minor Op.2: III. Adagio (attacca)

- Sonata No.1 for cello & piano in D minor Op.2: IV. Allegro non troppo, ma giocoso

- Sonata No.1 for cello & piano in E minor Op.38: I. Allegro non troppo

- Sonata No.1 for cello & piano in E minor Op.38: II. Allegretto quasi Menuetto

- Sonata No.1 for cello & piano in E minor Op.38: III. Allegro

- Sonata No.1 for cello & piano in A minor Op.52: I. Allegro

- Sonata No.1 for cello & piano in A minor Op.52: II. Adagio

- Sonata No.1 for cello & piano in A minor Op.52: III. Allegro Moderato

ROBERT FUCHS (1847–1927)

JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833–1897)

HEINRICH VON HERZOGENBERG (1843–1900)